Victor of Aveyron/th: Difference between revisions

MontessoriX (talk | contribs) (Created page with "นักสรีรวิทยาสมัยใหม่บางคนสันนิษฐานว่าความรู้สึกนั้นเป็นสัดส่วนที่แน่นอนกับระดับของอารยธรรม ฉันสงสัยว่าจะสามารถให้ข้อพิสูจน์ที่หนักแน่นกว่านี้เพื่อสนับสนุนความค...") |

MontessoriX (talk | contribs) (Created page with "การปรับปรุงการรับรู้รสชาติยังคงโดดเด่นยิ่งขึ้น สิ่งของเกี่ยวกับอาหารที่เด็กคนนี้ได้รับกินหลังจากมาถึงปารีสได้ไม่นานก็น่าขยะแขยงอย่างน่าตกใจ เขาติดตามพวกเขาไปทั...") |

||

| Line 111: | Line 111: | ||

นักสรีรวิทยาสมัยใหม่บางคนสันนิษฐานว่าความรู้สึกนั้นเป็นสัดส่วนที่แน่นอนกับระดับของอารยธรรม ฉันสงสัยว่าจะสามารถให้ข้อพิสูจน์ที่หนักแน่นกว่านี้เพื่อสนับสนุนความคิดเห็นนี้ได้ดีกว่าระดับความรู้สึกเล็กน้อยในอวัยวะรับสัมผัสซึ่งสังเกตได้ในกรณีของ Savage of Aveyron เราอาจพึงพอใจอย่างยิ่ง เพียงแค่ละสายตาจากคำอธิบายที่ฉันได้แสดงไปแล้ว ซึ่งตั้งอยู่บนข้อเท็จจริงที่ฉันได้มาจากแหล่งที่แท้จริงที่สุด ฉันจะเพิ่มที่นี่ในส่วนที่เกี่ยวข้องกับเรื่องเดียวกัน ข้อสังเกตที่น่าสนใจและสำคัญที่สุดของฉันเอง | นักสรีรวิทยาสมัยใหม่บางคนสันนิษฐานว่าความรู้สึกนั้นเป็นสัดส่วนที่แน่นอนกับระดับของอารยธรรม ฉันสงสัยว่าจะสามารถให้ข้อพิสูจน์ที่หนักแน่นกว่านี้เพื่อสนับสนุนความคิดเห็นนี้ได้ดีกว่าระดับความรู้สึกเล็กน้อยในอวัยวะรับสัมผัสซึ่งสังเกตได้ในกรณีของ Savage of Aveyron เราอาจพึงพอใจอย่างยิ่ง เพียงแค่ละสายตาจากคำอธิบายที่ฉันได้แสดงไปแล้ว ซึ่งตั้งอยู่บนข้อเท็จจริงที่ฉันได้มาจากแหล่งที่แท้จริงที่สุด ฉันจะเพิ่มที่นี่ในส่วนที่เกี่ยวข้องกับเรื่องเดียวกัน ข้อสังเกตที่น่าสนใจและสำคัญที่สุดของฉันเอง | ||

บ่อย ๆ ในฤดูหนาว ข้าพเจ้าได้เห็นเขาขณะกำลังนอนขบขันอยู่ในสวนของสถานสงเคราะห์คนหูหนวกเป็นใบ้ ทันใดนั้นหมอบลง เปลือยครึ่งท่อน บนสนามหญ้าเปียก และยังคงเปิดเผยในลักษณะนี้ เพราะ ชั่วโมงกันทั้งลมและฝน ไม่ใช่แค่ความหนาวเย็นเท่านั้น แต่ยังรวมถึงความร้อนที่รุนแรงที่สุดด้วย ซึ่งผิวหนังและความรู้สึกสัมผัสของเขาไม่แสดงความรู้สึกใดๆ เลย เกิดขึ้นบ่อยครั้ง เมื่อพระองค์อยู่ใกล้ไฟ และถ่านที่ยังคุกรุ่นหลุดออกจากตะแกรง พระองค์ก็ทรงฉวยมันขึ้นมา แล้วโยนกลับไปอีกครั้งด้วยความเฉยเมยอันหาที่สุดมิได้ เราพบเขามากกว่าหนึ่งครั้งในครัว เอามันฝรั่งออกจากน้ำเดือดในลักษณะเดียวกัน และฉันรู้ว่าในเวลานั้นเขามีผิวที่มีเนื้อละเอียดและละเอียดอ่อนมาก * | |||

* ฉันให้มันฝรั่งจำนวนมากแก่เขาซึ่งเคยเห็นเขาที่ St. Sernin; ดูเหมือนว่าพระองค์จะพอพระทัยในสายตานั้น จับมือพวกเขาแล้วโยนเข้าไปในกองไฟ หลังจากนั้นไม่นาน เขาก็นำมันกลับมาอีก และกินมันอย่างร้อนจัด | |||

* | |||

ฉันมักจะให้เขาดมปริมาณมากโดยไม่มีท่าทางตื่นเต้นที่จะจาม ซึ่งเป็นข้อพิสูจน์ที่สมบูรณ์ว่า ในกรณีนี้ ไม่มีระหว่างอวัยวะรับกลิ่นกับอวัยวะรับกลิ่นและการมองเห็น ความเห็นอกเห็นใจชนิดที่มักจะทำให้จามหรือน้ำตาไหล อาการสุดท้ายนี้ยังคงมีความรับผิดชอบน้อยกว่าอาการอื่นที่เกิดจากความเจ็บปวดทางจิตใจ และแม้จะมีความขัดแย้งนับไม่ถ้วน แม้จะมีการใช้มาตรการที่รุนแรงและดูโหดร้าย โดยเฉพาะอย่างยิ่งในช่วงเดือนแรกของชีวิตใหม่ของเขา ฉันก็ไม่เคยจับเขาร้องไห้เลยสักครั้ง | |||

จากประสาทสัมผัสทั้งหมดของเขา รถของเขาดูเหมือนจะไร้ความรู้สึกที่สุด แต่ที่น่าทึ่งคือเสียงที่เกิดจากการแตกร้าว วอลนัตซึ่งเป็นผลไม้ที่เขาชอบเป็นพิเศษ ปลุกความสนใจของเขาไม่เคยพลาด ความจริงของข้อสังเกตนี้อาจขึ้นอยู่กับ: แต่ถึงกระนั้น อวัยวะส่วนนี้กลับทรยศต่อการไม่รับรู้ต่อเสียงที่ดังที่สุด ต่อเสียงระเบิด เช่น เสียงปืน วันหนึ่งฉันยิงปืนสั้นสองกระบอกใกล้หูเขา คนแรกสร้างอารมณ์บางอย่าง แต่ครั้งที่สองทำให้เขาหันศีรษะด้วยความเฉยเมยอย่างเห็นได้ชัด | |||

ดังนั้น ในการเลือกบางกรณีเช่นนี้ซึ่งความบกพร่องของความสนใจสำหรับจิตใจอาจดูเหมือนต้องการความรู้สึกในอวัยวะนั้น ๆ ตรงกันข้ามกับที่ปรากฏครั้งแรกพบว่าพลังประสาทนี้อ่อนแออย่างน่าทึ่งใน ประสาทสัมผัสเกือบทั้งหมด แน่นอน มันเป็นส่วนหนึ่งของแผนการของฉันที่จะพัฒนาความรู้สึกสัมผัสด้วยทุกวิถีทางที่เป็นไปได้ และนำจิตใจไปสู่นิสัยของความสนใจ โดยเปิดเผยประสาทสัมผัสเพื่อรับความประทับใจที่มีชีวิตชีวาที่สุด | |||

จากวิธีการต่างๆ ที่ฉันใช้ ผลของความร้อนดูเหมือนจะทำให้ฉันบรรลุผลสำเร็จในลักษณะที่มีประสิทธิผลมากที่สุดต่อวัตถุที่ฉันมองเห็น เป็นแนวคิดที่นักสรีรวิทยา*, Lacus ยอมรับ Idea de l'homme ร่างกายและศีลธรรม | |||

*Laroche : วิเคราะห์ des fonctions du system encriveux และผู้ชายที่เรียนมาทางรัฐศาสตร์ ว่าชาวเมืองทางใต้เป็นหนี้บุญคุณต่อการกระทำของความร้อนบนผิว สำหรับความรู้สึกที่ประณีตซึ่งเหนือกว่าพวกเขาที่อาศัยอยู่ใน ภาคเหนือ ฉันใช้ประโยชน์จากสิ่งเร้านี้ในทุกวิถีทาง ฉันไม่คิดว่ามันเพียงพอสำหรับการจัดหาชุดโต๊ะคอม เตียงอุ่นๆ และที่พักให้ แต่ฉันคิดว่าจำเป็นต้องให้เขาแช่ในอ่างน้ำร้อนเป็นเวลาสองหรือสามชั่วโมงทุกวัน ระหว่างนั้นให้ดื่มน้ำ ที่อุณหภูมิเดียวกับน้ำในอ่างถูกฟาดลงบนศีรษะของเขาบ่อยครั้ง ฉันสังเกตเห็นว่าความร้อนและการอาบน้ำซ้ำๆ ตามมาด้วยผลที่ทำให้ร่างกายทรุดโทรมตามปกติ ซึ่งอาจเป็นไปตามที่คาดไว้ ฉันหวังว่าสิ่งนี้อาจเกิดขึ้น โดยเชื่อมั่นอย่างสมบูรณ์ว่า ในกรณีเช่นนี้ การสูญเสียกำลังของกล้ามเนื้อจะเป็นประโยชน์ต่อความรู้สึกทางประสาท | |||

*Laroche : | |||

* Fouqun: บทความ Sensibilité de l’Encyclopedie par ordre alphabétique. | |||

* Fouqun: | |||

* มองเตสกิเออ : Esprit des Lois, livre XIV. | |||

* | |||

ยังไงก็ตาม ถ้าผลที่ตามมานี้ไม่เกิดขึ้น ผลแรกก็ไม่ทำให้ความคาดหวังของฉันผิดหวัง หลังจากนั้นครู่หนึ่ง ชายหนุ่มผู้อำมหิตของเราดูเหมือนจะสัมผัสได้ถึงความหนาวเย็นอย่างเห็นได้ชัด เขาใช้มือของเขาเพื่อตรวจสอบอุณหภูมิของอ่างน้ำ และจะไม่ลงไปในอ่างหากไม่อุ่นเพียงพอ สาเหตุเดียวกันนี้ทำให้เขาเห็นคุณค่าประโยชน์ของเสื้อผ้าตัวนั้นในไม่ช้า ซึ่งก่อนหน้านี้เขาแทบไม่ได้หยิบยื่นให้เลย ทันทีที่เขาดูเหมือนจะรับรู้ถึงข้อดีของเสื้อผ้า มีกระท่อมเพียงขั้นตอนเดียวที่จำเป็นในการบังคับเขาให้แต่งตัวด้วยตัวเอง จุดจบนี้เกิดขึ้นได้ภายในเวลาไม่กี่วัน โดยปล่อยให้เขาสัมผัสความหนาวเย็นทุกเช้าในระยะที่เสื้อผ้าเอื้อมถึง จนกว่าเขาจะค้นพบวิธีการสวมมันด้วยตัวเอง ประโยชน์ที่คล้ายคลึงกันมากทำให้เกิดความมุ่งหมายในการทำให้เขามีนิสัยเรียบร้อยและสะอาด เนื่องจากความแน่นอนของการผ่านคืนบนเตียงที่เย็นและเปียกชื้นทำให้เขาจำเป็นต้องลุกขึ้นเพื่อสนองความต้องการตามธรรมชาติของเขา | |||

นอกจากการใช้เครื่องอุ่นแล้ว ฉันได้กำหนดการใช้แรงเสียดทานแบบแห้งกับกระดูกสันหลังและแม้แต่การจั๊กจี้บริเวณบั้นเอว วิธีสุดท้ายนี้ดูเหมือนจะมีแนวโน้มกระตุ้นมากที่สุด: ฉันพบว่าตัวเองอยู่ภายใต้ความจำเป็นในการห้ามใช้มันเมื่อผลของมันไม่ จำกัด อยู่ที่การผลิตอารมณ์ที่น่าพึงพอใจอีกต่อไป แต่ดูเหมือนจะขยายตัวเองไปยังอวัยวะของรุ่นและเพื่อบ่งบอก อันตรายบางอย่างในการปลุกความรู้สึกของวัยแรกรุ่นก่อนวัยอันควร สำหรับสารกระตุ้นต่างๆ เหล่านี้ ฉันคิดว่ามันเหมาะสมแล้วที่จะขอความช่วยเหลือจากความตื่นเต้นที่เกิดจากความรู้สึกทางใจ คนที่เขาอ่อนแอเพียงคนเดียวในช่วงเวลานี้ถูกกักขังไว้สองคน ความสุขและความโกรธ ข้าพเจ้ายั่วยุอย่างหลัง ในระยะที่ห่างไกลเท่านั้น เพื่อที่ว่าอาการหวาดระแวงอาจรุนแรงขึ้น และมักจะเข้าร่วมด้วยท่าทางที่สมเหตุสมผลของความยุติธรรม บางครั้งข้าพเจ้าตั้งข้อสังเกตว่า ในช่วงเวลาที่เขาขุ่นเคืองใจอย่างรุนแรงที่สุด ความเข้าใจของเขาดูเหมือนจะขยายใหญ่ขึ้นชั่วคราว ซึ่งเสนอแนะทางอันแยบยลบางอย่างแก่เขาในการปลดเปลื้องตัวเองจากความลำบากใจที่ไม่น่ายินดี ครั้งหนึ่งขณะที่เราพยายามเกลี้ยกล่อมให้เขาใช้อ่างอาบน้ำ ขณะที่มันอุ่นพอประมาณ การขอร้องซ้ำๆ และเร่งด่วนของเราทำให้เขาหลงใหลอย่างรุนแรง ด้วยอารมณ์เช่นนี้ เมื่อเห็นว่าการปกครองของเขาไม่น่าเชื่อถือเลย ด้วยการทดลองบ่อยครั้งซึ่งเขาใช้นิ้วสัมผัสด้วยตัวเองเกี่ยวกับความเย็นของน้ำ เขาจึงหันกลับมาหาเธอในลักษณะที่เร่งรัด จับมือเธอแล้วกระโดดลงไป มันลงอ่างด้วยตัวมันเอง พูดถึงอีกกรณีหนึ่งในลักษณะนี้: วันหนึ่งขณะที่เขานั่งอยู่บนเก้าอี้ออตโตมันในห้องเรียนของฉัน ฉันวางตัวเองไว้ข้างๆ เขา และระหว่างเรามี Leyden phial ซึ่งตั้งข้อหาเล็กน้อย ความตกใจเล็กน้อยที่เขาได้รับจากมันทำให้เขาหันเหจากภวังค์ เมื่อสังเกตเห็นความไม่สบายใจที่เขาแสดงออกเมื่อเข้าใกล้เครื่องมือนี้ ฉันคิดว่าเขาจะถูกชักจูงให้จับลูกบิดเพื่อเอามันออกไปให้ไกลขึ้น เขาใช้มาตรการที่รอบคอบกว่ามาก นั่นคือ สอดมือเข้าไปในช่องเปิดของเสื้อโค้ท และถอยออกมาสองสามนิ้ว จนกระทั่งต้นขาของเขาไม่สัมผัสกับชั้นเคลือบด้านนอกของขวดอีกต่อไป ฉันเข้าไปใกล้เขาเป็นครั้งที่สอง และวางฟีลไว้ระหว่างเราอีกครั้ง สิ่งนี้ทำให้เกิดการเคลื่อนไหวอีกครั้งในส่วนของเขาและอีกอย่างสำหรับฉัน อุบายเล็ก ๆ น้อย ๆ นี้กินเวลาจนกระทั่งถูกผลักไปที่ปลายสุดของโซฟา และถูกจำกัดโดยผนังด้านหลัง ก่อนที่โต๊ะ และด้านข้างของฉันโดยเครื่องจักรที่มีปัญหา มันเป็นไปไม่ได้ที่เขาจะเคลื่อนไหวอีก จากนั้นเขาก็ฉวยจังหวะที่ฉันกำลังยื่นแขนไปจับเขา แล้ววางข้อมือของฉันลงบนลูกบิดโถอย่างคล่องแคล่ว แน่นอนว่าฉันได้รับการปลดประจำการแทนเขา | |||

แต่ถ้าเมื่อไรก็ตาม แม้ว่าฉันจะสนใจและรักเด็กกำพร้าคนนี้อย่างมีชีวิตชีวา แต่ฉันคิดว่ามันเหมาะสมที่จะปลุกความโกรธของเขา ฉันไม่ปล่อยให้โอกาสเดียวที่จะหนีจากฉันไปให้เขาเพลิดเพลิน และมัน และจะต้องเป็น สารภาพว่า เพื่อให้ประสบความสำเร็จในเรื่องนี้ ไม่มีความจำเป็นต้องขอความช่วยเหลือด้วยวิธีใด ๆ ที่เข้าร่วมด้วยความยากลำบากหรือค่าใช้จ่าย ลำแสงของดวงอาทิตย์ รับกระจก สะท้อนในห้องของเขา และโยนขึ้นไปบนเพดาน แก้วน้ำซึ่งถูกทำให้ตกลงมาทีละหยดจากความสูงระดับหนึ่งบนปลายนิ้วมือของเขาในขณะที่เขากำลังอาบน้ำ และแม้กระทั่งน้ำนมเล็กน้อยซึ่งบรรจุอยู่ในหม้อไม้ซึ่งวางไว้ที่ปลายสุดของอ่างของเขา และซึ่งการสั่นไหวของน้ำก็เคลื่อนไหว ทำให้เขาตื่นเต้นในอารมณ์แห่งความสุขที่มีชีวิตชีวา ซึ่งแสดงออกมาด้วยเสียงโห่ร้องและเสียงปรบมือของ มือของเขา: สิ่งเหล่านี้เป็นวิธีการเกือบทั้งหมดที่จำเป็นในการทำให้มีชีวิตชีวาและมีความสุข มักจะเกือบทำให้มึนเมา เด็กธรรมดาๆ ในธรรมชาติคนนี้ | |||

สิ่งดังกล่าวคือตัวกระตุ้นรวมทั้งทางร่างกายและทางศีลธรรมซึ่งฉันทำงานเพื่อพัฒนาความรู้สึกสัมผัสของอวัยวะของเขา วิธีการเหล่านี้เกิดขึ้นหลังจากช่วงเวลาสั้น ๆ สามเดือน ความตื่นเต้นทั่วไปของพลังที่ละเอียดอ่อนทั้งหมดของเขา เพราะเวลานั้น สัมผัสนั้นแสดงความรู้สึกสัมผัสของร่างกายได้ทั้งหมด ไม่ว่าจะร้อนหรือเย็น เรียบหรือหยาบ นุ่มหรือแข็ง ในช่วงเวลานั้น ฉันสวมกางเกงชั้นในกำมะหยี่ ซึ่งดูเหมือนเขาจะชอบใจในการดึงมือของเขา โดยการสัมผัสของเขาทำให้เขาแน่ใจว่ามันฝรั่งของเขาต้มเพียงพอหรือไม่: เขาหยิบมันขึ้นมาจากก้นหม้อด้วยช้อน จากนั้นเขาก็ใช้นิ้วจับมันซ้ำๆ แล้วตัดสินใจจากระดับความแข็งหรืออ่อนว่าจะกินหรือจะโยนกลับลงไปในน้ำเดือด เมื่อยื่นกระดาษให้เขาเพื่อจุดเทียน เขาไม่ค่อยรอจนกระทั่งไส้ตะเกียงติดไฟ แต่รีบโยนกระดาษทิ้งก่อนที่เปลวไฟจะใกล้จะสัมผัสนิ้วของเขา หลังจากถูกชักจูงให้ผลักหรือแบกร่างกายที่แข็งหรือหนัก จู่ๆ เขาก็แทบจะไม่ยอมชักมือออก มองดูปลายนิ้วมืออย่างตั้งอกตั้งใจ แม้ว่านิ้วจะไม่ฟกช้ำหรือช้ำเลยแม้แต่น้อย ได้รับบาดเจ็บและวางไว้ในลักษณะสบาย ๆ ในการเปิดเสื้อกั๊กของเขา ประสาทสัมผัสในการดมกลิ่นได้รับการปรับปรุงในทำนองเดียวกัน อันเป็นผลมาจากการเปลี่ยนแปลงที่เกิดขึ้นในร่างของเขา การระคายเคืองน้อยที่สุดที่ใช้กับอวัยวะนี้ ตื่นเต้น จาม; และจากความสยดสยองที่เขาถูกจับในครั้งแรกที่สิ่งนี้เกิดขึ้น ฉันคิดว่ามันเป็นเรื่องใหม่สำหรับเขาโดยสิ้นเชิง เขาตื่นเต้นมากจนแทบจะทิ้งตัวลงบนเตียง | |||

การปรับปรุงการรับรู้รสชาติยังคงโดดเด่นยิ่งขึ้น สิ่งของเกี่ยวกับอาหารที่เด็กคนนี้ได้รับกินหลังจากมาถึงปารีสได้ไม่นานก็น่าขยะแขยงอย่างน่าตกใจ เขาติดตามพวกเขาไปทั่วห้อง และกินมันจากมือของเขาที่เปรอะเปื้อนไปด้วยสิ่งสกปรก แต่ในช่วงเวลาที่ฉันกำลังพูดอยู่นี้ นอนโยนของในจานของเขาทิ้งตลอดเวลา ถ้ามีเศษดินหรือฝุ่นตกลงบนสัตว์เลี้ยง และหลังจากที่เขาหักวอลนัทของเขาแล้ว เขาก็ใช้ความอุตสาหะในการทำความสะอาดมันด้วยวิธีที่ประณีตและละเอียดอ่อนที่สุด | |||

ที่โรคภัยไข้เจ็บ แม้แต่โรคที่เป็นผลที่หลีกเลี่ยงไม่ได้และน่าลำบากใจซึ่งเกิดจากสภาวะของอารยธรรมก็เพิ่มประจักษ์พยานของพวกเขาในการพัฒนาหลักธรรมแห่งชีวิต ในช่วงต้นฤดูใบไม้ผลิ เด็กดุร้ายของเราได้รับผลกระทบจากความหนาวเย็นอย่างรุนแรง และไม่กี่สัปดาห์หลังจากนั้น การโจมตีสองครั้งในลักษณะเดียวกัน การโจมตีหนึ่งครั้งเกือบจะสำเร็จในทันที | |||

อย่างไรก็ตามอาการเหล่านี้จำกัดอยู่เฉพาะในอวัยวะบางส่วนเท่านั้น สายตาและการได้ยินเหล่านั้นไม่ได้รับผลกระทบจากพวกมันเลย เห็นได้ชัดว่าเพราะประสาทสัมผัสทั้งสองนี้ ซึ่งเรียบง่ายกว่าส่วนอื่นๆ มาก ต้องใช้เวลาหนึ่งนาทีและการศึกษาที่ยืดเยื้อมากขึ้น ดังที่จะปรากฏในภาคต่อของประวัติศาสตร์นี้ การปรับปรุงประสาทสัมผัสทั้ง 3 ที่เกิดขึ้นพร้อมกันซึ่งเป็นผลมาจากสารกระตุ้นที่ใช้กับผิวหนัง ในเวลาเดียวกันที่ประสาทสัมผัสทั้งสองยังคงอยู่นิ่ง เป็นข้อเท็จจริงที่สำคัญและสมควรได้รับความสนใจเป็นพิเศษจากนักสรีรวิทยา ดูเหมือนว่าจะพิสูจน์ได้ว่าสิ่งที่ปรากฏจากแหล่งอื่นไม่น่าจะเป็นไปได้ว่าความรู้สึกสัมผัสกลิ่นและรสเป็นเพียงการดัดแปลงอวัยวะของผิวหนังที่แตกต่างกัน ในขณะที่ส่วนหูและตา ซึ่งไม่ได้รับการสัมผัสจากภายนอกน้อยกว่า และถูกห่อหุ้มด้วยสิ่งปกคลุมที่ซับซ้อนกว่ามาก อยู่ภายใต้กฎแห่งการปรับปรุงแก้ไขอื่นๆ และในบัญชีนั้น ควรได้รับการพิจารณาว่าเป็นประเภทที่แตกต่างกันโดยสิ้นเชิง | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | <div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | ||

Revision as of 08:41, 19 July 2023

สรุปย่อ

เด็กชายที่เรียกว่า ป่าแห่งอาวีรงถูกค้นพบในป่าแห่งคอน ในประเทศฝรั่งเศสและถูกจับกุมโดยผู้ที่เล่นกีฬาสามคน เขาหนีจากคนที่เอาเข้าไปและมีชีวิตที่ลำบากในฤดูหนาวของภูเขา ในที่สุดเขาได้พบที่กำบังและถูกส่งไปที่สถานที่ต่างๆเพื่อดูแล ในกรุงปารีสเขากลายเป็นสิ่งที่น่าสนใจแต่แสดงพฤติกรรมที่เป็นอันตรายและขาดทักษะทางสังคมและทางปัญญา อย่างไรก็ตาม ยังคงมีความหวังในการศึกษาและฟื้นฟูเขา และเขาได้ถูกใช้งานโดยผู้เขียน

ข้อมูล

- 🌳 เด็กป่าแห่งอาวีรงถูกค้นพบในป่าแห่งคอน ฝรั่งเศส และเลี้ยงด้วยเมล็ดออคอร์นและรากพืช

- 🏞️ หลังจากถูกจับกุมและดูแลชั่วคราว เขาหนีไปอาศัยอยู่ในภูเขาในช่วงฤดูหนาวรุนแรง เขาสวมเสื้อที่เป่าลายเสื้อเป่าอย่างเดียว

- 🏘️ เขาได้ผู้ที่เป็นโจรตามติดมาเป็นชีวิตรอด มองหาที่อยู่กลางคืนและเข้าชมหมู่บ้านในช่วงวัน

- 🏥 เมื่อถึง St. Sernin และ Rodez เด็กป่าแห่งอาวีรงถูกส่งไปยังโรงพยาบาลที่นี่ ที่มองเห็นพฤติกรรมที่เป็นอันตรายและเลือกที่

- 🗼 เด็กป่าแห่งอาวีรงมาถึงปารีสในปี 1799 เข้าท่าความคาดหวังแต่แสดงพฤติกรรมที่ไม่เป็นที่พอใจและไม่เป็นสังคม

- 🧠 เขาถูกบรรยายว่ามีฟังก์ชันสามัญที่อยู่ในสภาวะที่เฉื่อยชาและมีประสาทที่จำกัดและไม่มีความสนใจ ความจำ การตัดสินใจ หรือความสามารถในการสื่อสาร

- 📚 นอกจากคำวินิจฉัยที่ไม่ดี ผู้เขียนพร้อมกับผู้ดูแลสถาบันชาวตกแต่งชายใหญ่ก็เชื่อว่ายังมีความหวังในการศึกษาและฟื้นฟูเด็กป่าแห่งอาวีรง

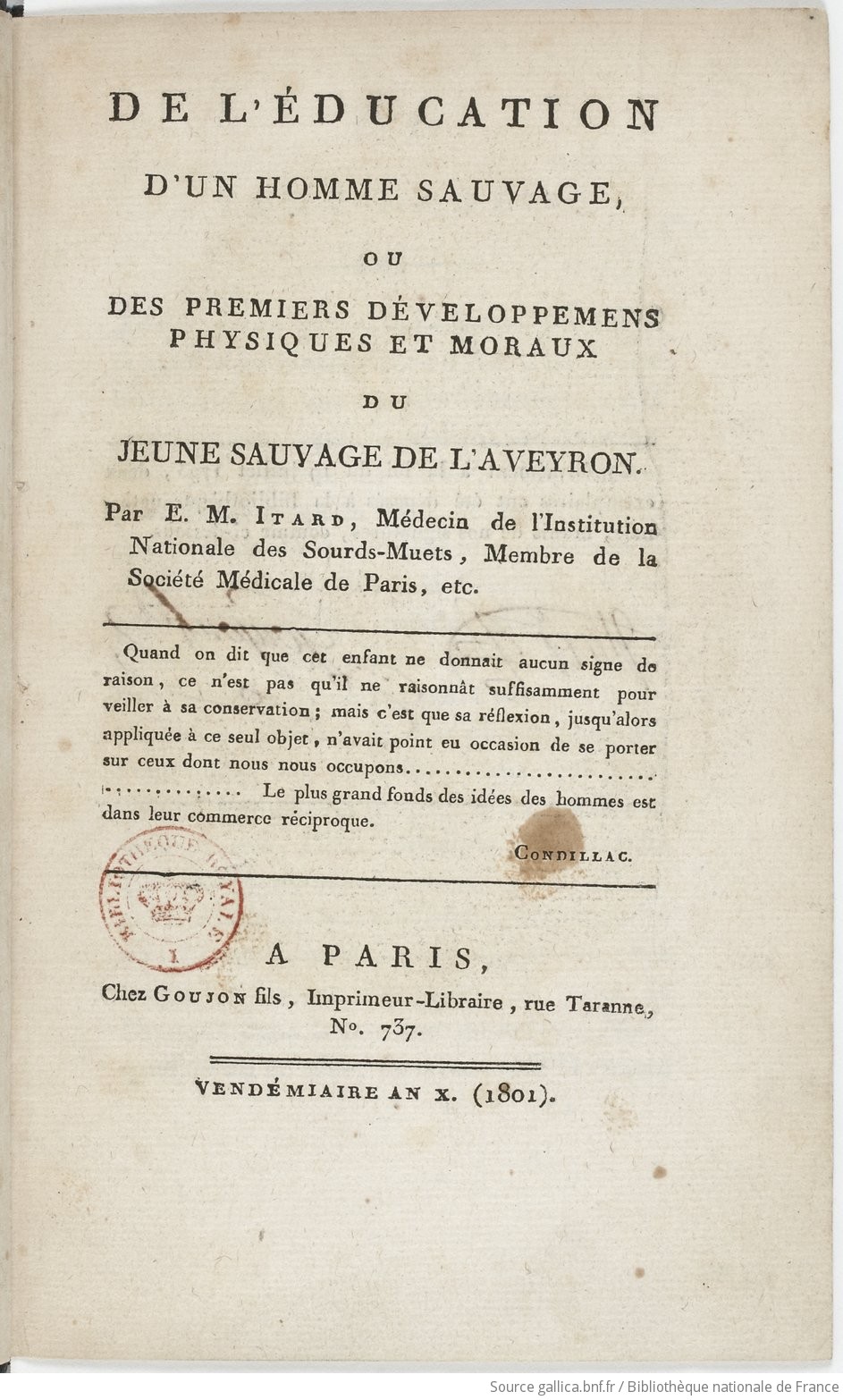

ของการเลี้ยงชายป่าซึ่งเป็นการพัฒนาทางร่างกายและศีลธรรมครั้งแรกของ Young Sauvage of Aveyron โดย E.M. Itard, แพทย์แห่งสถาบันแห่งชาติเพื่อคนหูหนวก, สมาชิกสมาคมการแพทย์แห่งปารีส ฯลฯ

ของการเลี้ยงชายป่าซึ่งเป็นการพัฒนาทางร่างกายและศีลธรรมครั้งแรกของ Young Sauvage of Aveyron โดย E.M. Itard, แพทย์แห่งสถาบันแห่งชาติเพื่อคนหูหนวก, สมาชิกสมาคมการแพทย์แห่งปารีส ฯลฯ

เมื่อมีคนกล่าวว่าเด็กคนนี้ไม่ได้ให้เหตุผล ไม่ใช่ว่าเขาไม่มีเหตุผลเพียงพอที่จะดูแลการรักษาของเขา แต่เป็นเพราะการไตร่ตรองของเขาซึ่งมาจนถึงบัดนี้ได้นำไปใช้กับวัตถุเพียงชิ้นเดียวนี้ ไม่มีโอกาสที่จะมุ่งเน้นไปที่ผู้ที่เรากำลังติดต่อกับ ... … รากฐานที่ยิ่งใหญ่ที่สุดของความคิดของผู้ชายอยู่ที่การค้าขายซึ่งกันและกัน

— คอนดิแลค

ในปารีส, Chez Goujon fils, Printer-Bookseller, rue Taranne, หมายเลข 737, Vendémiaire ปี x. (1801).

ตามกฎหมายของวันที่ 19 กรกฎาคม พ.ศ. 2336 หอสมุดแห่งชาติได้มอบสำเนาสองชุดพร้อมลายเซ็นของเราดังต่อไปนี้

คำนำ

ถูกโยนลงมาบนโลกนี้ โดยปราศจากแรงกาย และไม่มีความคิดโดยกำเนิด ไม่สามารถปฏิบัติตามกฎหมายรัฐธรรมนูญขององค์กรของเขาเองได้ ซึ่งเรียกเขาว่าระบบลำดับที่หนึ่งของสิ่งมีชีวิต มนุษย์จะพบแต่สถานที่อันโดดเด่นในสังคมเท่านั้น สำหรับเขาในธรรมชาติและจะปราศจากอารยธรรม หนึ่งในสัตว์ที่อ่อนแอที่สุดและฉลาดน้อยที่สุด: ความจริง ไม่ต้องสงสัยเลย ถูกแฮ็กอย่างดี แต่ยังไม่ได้รับการพิสูจน์อย่างจริงจัง บรรดานักปรัชญาที่กล่าวคำนี้เป็นครั้งแรก บรรดาผู้ที่สนับสนุนและเผยแพร่ในเวลาต่อมา ได้ให้หลักฐานเป็นข้อพิสูจน์ถึงสภาพร่างกายและศีลธรรมของชนเผ่าเร่ร่อนบางเผ่า ซึ่งพวกเขามองว่าไร้อารยธรรม เพราะพวกเขาไม่ได้ขวางทางเรา เพื่อดึงลักษณะของมนุษย์ในสภาพบริสุทธิ์ ไม่ สิ่งใดก็ตามที่พูดเกี่ยวกับมัน ไม่มีอีกแล้วที่เราจะต้องค้นหาและศึกษามัน ในฝูงชนป่าเถื่อนที่พเนจรที่สุด เช่นเดียวกับในประเทศที่มีอารยธรรมมากที่สุดของยุโรป มนุษย์เป็นเพียงสิ่งที่เขาถูกสร้างมาให้เป็นเท่านั้น จำเป็นต้องเลี้ยงดูโดยเพื่อนของเขาเขาได้ทำสัญญากับนิสัยและความต้องการของพวกเขา ความคิดของเขาไม่ใช่ของเขาอีกต่อไป เขามีอภิสิทธิ์ที่ดีที่สุดของเผ่าพันธุ์ของเขา ความอ่อนไหวในการพัฒนาความเข้าใจของเขาโดยแรงของการเลียนแบบและอิทธิพลของสังคม

ดังนั้น เราควรแสวงหาต้นแบบของชายผู้อำมหิตจริงๆ จากที่อื่น ซึ่งไม่มีหนี้อะไรให้ทัดเทียมเขา และหาความคิดเห็นของเราเกี่ยวกับเขาจากประวัติเฉพาะของบุคคลไม่กี่คน ซึ่งในช่วงศตวรรษที่สิบเจ็ดและที่ มีการค้นพบต้นที่สิบแปดในช่วงเวลาต่างๆ กัน อาศัยอยู่ในสภาพสันโดษท่ามกลางป่า ซึ่งพวกเขาถูกทิ้งตั้งแต่อายุยังน้อย *

- Linnaeus สร้างจำนวนเป็นสิบและแสดงให้เห็นว่าพวกมันก่อตัวเป็นสายพันธุ์มนุษย์ที่หลากหลาย (ซิสเต็ม เดอ ลา เนเจอร์)

แต่ในเวลานี้ความก้าวหน้าของวิทยาศาสตร์เป็นไปอย่างเชื่องช้า นักเรียนที่อุทิศตนให้กับทฤษฎีและสมมติฐานที่ไม่แน่นอน และการทำงานเฉพาะของตู้เสื้อผ้า การสังเกตที่แท้จริงนั้นถือว่าไม่มีค่า ข้อเท็จจริงที่น่าสนใจเหล่านี้มีแนวโน้มที่จะปรับปรุงประวัติศาสตร์ธรรมชาติของมนุษย์เพียงเล็กน้อย ทุกสิ่งที่นักเขียนร่วมสมัยทิ้งไว้ให้นั้นถูกจำกัดไว้เพียงรายละเอียดเล็กน้อยที่ไม่สำคัญ ซึ่งผลที่เด่นชัดที่สุดและโดยทั่วไปคือ บุคคลเหล่านี้ไม่หวั่นไหวต่อการปรับปรุงที่เด่นชัดใดๆ เห็นได้ชัดว่าด้วยเหตุนี้ เพราะพวกเขาถูกนำไปใช้โดยไม่คำนึงถึงความแตกต่างของอวัยวะของพวกเขาเลยแม้แต่น้อย นั่นคือระบบการศึกษาปกติ หากรูปแบบการสอนนี้ประสบความสำเร็จอย่างสมบูรณ์กับหญิงสาวอำมหิตที่พบในฝรั่งเศสเมื่อต้นศตวรรษที่แล้ว เหตุผลก็คือ เธออาศัยอยู่ในป่ากับเพื่อนของเธอแล้ว เธอเป็นหนี้บุญคุณต่อความสัมพันธ์ที่เรียบง่ายนี้สำหรับการพัฒนาบางอย่าง ปัญญาอันเฉียบแหลมของเธอ ในความเป็นจริง การศึกษาเช่น Condillac * พูดถึง เมื่อเขาคิดว่าเด็กสองคนถูกทอดทิ้งให้อยู่อย่างสันโดษ ในกรณีนี้ อิทธิพลเพียงอย่างเดียวของการอยู่ร่วมกันของพวกเขาจะต้องให้ขอบเขตแก่การใช้ความจำและจินตนาการของพวกเขา และชักนำพวกเขา เพื่อสร้างป้ายประดิษฐ์จำนวนน้อย

- Essai sur l'origine des connaissances humaines, 2e partie, Sect. 1 ครั้ง

มันเป็นข้อสันนิษฐานที่แยบยล ซึ่งมีเหตุผลพอสมควรจากประวัติของเด็กหญิงคนเดียวกันนี้ ซึ่งความทรงจำของเธอพัฒนาไปไกลจนสามารถย้อนรอยเหตุการณ์ต่างๆ ของที่อยู่อาศัยของเธอในป่าได้ และในลักษณะที่สั้นที่สุด โดยเฉพาะอย่างยิ่งการเสียชีวิตอย่างทารุณของเพื่อนหญิงของเธอ *

- เด็กหญิงคนนี้ถูกจับได้ในปี ค.ศ. 1731 ในบริเวณรอบๆ Chalons-sur-Marne และได้รับการศึกษาในคอนแวนต์ภายใต้ชื่อ Mademoiselle Leblanc เธอเล่าทันทีที่เธอพูดได้ว่าเธออาศัยอยู่ในป่ากับเพื่อนคนหนึ่ง และโชคไม่ดีที่เธอถูกคนใจร้ายฆ่าเธอ อยู่มาวันหนึ่งเมื่อพบลูกแก้วอยู่ใต้เท้าของพวกเขา พวกเขาโต้เถียงกันเรื่องการครอบครองมันแต่เพียงผู้เดียว

- ราซีน, Poeme de Religion.

เมื่อปราศจากข้อได้เปรียบเหล่านี้ เด็กที่เหลือจึงพบว่าอยู่ในสถานะของความเป็นปัจเจกบุคคล ประวัติศาสตร์นี้แม้จะเป็นเหตุการณ์ที่คลุมเครือมาก แต่ก็ไม่ค่อยดีนัก หากมีใครอนุมานจากมันได้ ในตอนแรก อะไรไม่สำคัญ และในลำดับต่อไป อะไรเหลือเชื่อ มันนำเสนอเพียงจำนวนเล็กน้อย รายการที่ควรแจ้งให้ทราบ; ที่น่าทึ่งที่สุดคือ ความรู้ที่เด็กป่าเถื่อนคนนี้มี คือการระลึกถึงความทรงจำของเธอเกี่ยวกับสถานการณ์ของสภาพก่อนหน้านี้ของเธอที่ไม่อาจยอมรับได้อย่างสมบูรณ์ ซึ่งต้องทำให้ยุ่งเหยิง สมมุติว่าพวกเขามุ่งสู่การศึกษาของพวกเขา ความพยายามร่วมกันทั้งหมดของศีลธรรม ปรัชญาที่แทบจะไม่เกิดขึ้นในวัยเด็ก ยังไม่ถูกรบกวนด้วยอคติของความคิดที่มีมาแต่กำเนิด และโดยทฤษฎีการแพทย์ ทรรศนะซึ่งจำเป็นต้องมีการหดตัวโดยหลักคำสอนโดยสิ้นเชิง ไม่อาจสะท้อนความคิดเชิงปรัชญาเกี่ยวกับโรคภัยของความเข้าใจได้ ได้รับความช่วยเหลือจากการวิเคราะห์และให้การสนับสนุนซึ่งกันและกัน วิทยาศาสตร์ทั้งสองนี้ในยุคสมัยของเราได้กำจัดข้อผิดพลาดเก่า ๆ ของพวกเขาและก้าวหน้าอย่างมากไปสู่ความสมบูรณ์แบบ ในบัญชีนี้ เรามีเหตุผลที่จะหวังว่า หากบุคคลที่คล้ายกันถูกนำเสนอต่อบุคคลที่เราพูดถึง พวกเขาจะใช้ทรัพยากรทั้งหมดที่ได้มาจากความรู้จริงของพวกเขา เพื่อก่อให้เกิดการพัฒนาทางร่างกายและศีลธรรม : หรืออย่างน้อย ถ้าแอปพลิเคชันนี้พิสูจน์ไม่ได้หรือไร้ผล ก็จะพบคนในยุคนี้ที่เฝ้าสังเกตบุคคลซึ่งรวบรวมประวัติของสิ่งมีชีวิตที่น่าอัศจรรย์อย่างรอบคอบ จะค้นหาว่าเขาเป็นใคร และอนุมานจากอะไร กำลังต้องการให้เขา จำนวนเงินที่ยังไม่ได้คำนวณ ของความรู้และความคิดเหล่านั้นซึ่งมนุษย์เป็นหนี้บุญคุณต่อการศึกษาของเขา

บางทีฉันอาจกล้าสารภาพว่าเป็นความตั้งใจของฉันที่จะทำวัตถุสำคัญทั้งสองนี้ให้สำเร็จ? แต่ไม่ต้องถามฉันว่าฉันประสบความสำเร็จในการออกแบบของฉันแล้วหรือยัง นี่จะเป็นคำถามที่เกิดก่อนเวลาอันควร ซึ่งข้าพเจ้าไม่สามารถตอบได้ในอนาคตอันใกล้นี้ อย่างไรก็ตาม ฉันควรจะรอมันอย่างเงียบๆ โดยไม่ต้องการให้สาธารณชนรับรู้ถึงผลงานของฉัน หากมันไม่ได้เป็นไปตามความปรารถนาของฉันมากเท่ากับหน้าที่ของฉันที่จะพิสูจน์โดยความสำเร็จของการทดลองครั้งแรกของฉันว่า เด็กที่ฉันสร้างให้นั้นไม่ใช่เด็กงี่เง่าสิ้นหวังอย่างที่เชื่อกันทั่วไป แต่เป็นเด็กที่น่าหลงใหลซึ่งสมควรได้รับความสนใจจากผู้สังเกตการณ์ในทุกมุมมอง การบริหาร.

1.0. - จากพัฒนาการครั้งแรกของ Sauvage De L'Aveyron รุ่นเยาว์

อายุสิบเอ็ดหรือสิบสองปีซึ่งคนหนึ่งเคยเห็นเมื่อไม่กี่ปีก่อนในป่า La Caune เปลือยเปล่ามองหาลูกโอ๊กและรากที่เขาเคยกินในปี 7 พบกับนักล่าสามคนที่ยึดมัน เมื่อมันปีนต้นไม้เพื่อหนีการไล่ล่าของพวกเขา นำไปยังหมู่บ้านใกล้เคียง และได้รับมอบหมายให้ดูแลหญิงม่าย เขาจึงหนีรอดไปได้ในปลายสัปดาห์ ไปถึงภูเขา ที่ซึ่งเขาเดินเตร่ในฤดูหนาวอันหนาวเหน็บที่สุด โดยแต่งกายแทนที่จะสวมเสื้อเป็นผ้าขี้ริ้ว ในเวลากลางคืนในที่เปลี่ยวใกล้ในตอนกลางวันหมู่บ้านใกล้เคียงจึงนำชีวิตที่หลงทางมาจนถึงวันที่เขาเข้าสู่บ้านพักอาศัยในตำบลแซงต์แซร์นิน เขาถูกพาไปที่นั่นอีกครั้ง ดูและดูแลเป็นเวลาสองหรือสามวัน ย้ายจากที่นั่นไปที่บ้านพักรับรองของ Saint-Afrique จากนั้นไปที่ Rhodez ซึ่งเขาถูกเก็บไว้เป็นเวลาหลายเดือน ระหว่างที่ประทับอยู่ ณ ที่ต่างๆ เหล่านี้ เราเห็นท่านดุร้ายเสมอกัน ใจร้อน คล่องตัว หาทางหนีอยู่เรื่อย ๆ และจัดวางสิ่งของให้น่าสังเกตที่สุด รวบรวมโดยพยานที่คู่ควรแก่ศรัทธา ซึ่งข้าพเจ้าจะไม่ลืมที่จะนำมา ย้อนกลับไปในบทความของ Essay นี้ ซึ่งพวกเขาจะสามารถเกิดขึ้นได้ด้วยความได้เปรียบมากขึ้น [4] รัฐมนตรีผู้พิทักษ์วิทยาศาสตร์เชื่อว่าคุณธรรมสามารถดึงความกระจ่างจากเหตุการณ์นี้ได้ มีคำสั่งให้พาเด็กคนนี้ไปปารีส เขามาถึงที่นั่นเมื่อปลายปีที่ 8 ภายใต้การแนะนำของชายชราผู้น่าสงสารและน่านับถือซึ่งต้องจากเขาไปหลังจากนั้นไม่นานสัญญาว่าจะกลับไปรับเขาและทำหน้าที่เป็นบิดาของเขาหากสมาคมจะ ไม่เคยทิ้งเขา

[4] ทุกสิ่งที่ฉันเพิ่งพูดไป และสิ่งที่ฉันจะพูดในภายหลังเกี่ยวกับเรื่องราวของเด็กคนนี้ ก่อนที่เขาจะอยู่ในปารีส ได้รับการรับรองโดยรายงานอย่างเป็นทางการของพลเมือง Guiraud และ Constant de Saint-Estève กรรมาธิการของรัฐบาลคนแรก ใกล้แคว้นแซงต์-อาฟริกา ที่สองใกล้กับแซงต์-แซร์นิน และจากการสังเกตของพลเมืองโบนาแตร์ ศาสตราจารย์ด้านประวัติศาสตร์ธรรมชาติที่โรงเรียนกลางของภาควิชาอเวย์รอน ได้บันทึกไว้อย่างละเอียดในบันทึกประวัติศาสตร์ของเขาที่ Savage of Aveyron ปารีส ปี 8

นักบวชผู้มีชื่อเสียงในฐานะผู้อุปถัมภ์วิทยาศาสตร์และวรรณกรรมทั่วไป คิดว่าจากเหตุการณ์นี้ แสงสว่างใหม่อาจถูกโยนทิ้งไปในวิทยาศาสตร์ศีลธรรมของมนุษย์ที่ได้รับอนุญาตหรือเด็กที่จะถูกนำไปปารีส เขาไปถึงที่นั่นประมาณปลายปี พ.ศ. 2342 ภายใต้การดูแลของชายชราผู้น่าสงสารแต่มีหน้ามีตา ผู้ซึ่งจำเป็นต้องจากเขาไปหลังจากนั้นไม่นาน เขาสัญญาว่าจะกลับมาและเป็นพ่อของเขาหากโกหก สมควรถูกสังคมทอดทิ้ง

ความคาดหวังที่ยอดเยี่ยมที่สุดแต่ไม่สมเหตุสมผลนั้นเกิดขึ้นจากผู้คนในปารีสที่เคารพผู้อำมหิตแห่ง Aveyron ก่อนที่เขาจะมาถึง[5]

[5] หากว่าด้วยการแสดงออกว่าป่าเถื่อน เราเข้าใจคนไร้อารยธรรมมาจนบัดนี้แล้ว เราจะเห็นพ้องกันว่าผู้ที่ไม่สมควรได้รับนิกายนี้อย่างเข้มงวดยิ่งขึ้นไปอีก ข้าพเจ้าจะเก็บชื่อนี้ไว้สำหรับชื่อนี้ จนกว่าข้าพเจ้าจะได้แจ้งเหตุผลที่กำหนดให้ข้าพเจ้าให้ชื่อนั้นอีก

ผู้คนที่อยากรู้อยากเห็นหลายคนต่างคาดหวังถึงความยินดีอย่างยิ่งที่ได้เฝ้าดูสิ่งที่จะทำให้เขาประหลาดใจเมื่อเห็นของดีในเมืองหลวง ในทางกลับกัน หลายคนโดดเด่นในเรื่องความเข้าใจที่เหนือกว่า โดยลืมไปว่าอวัยวะของเรามีความยืดหยุ่นน้อยกว่า และเลียนแบบได้ยากกว่า ตามสัดส่วนที่มนุษย์ถูกพรากจากสังคมและช่วงวัยเด็กของเขา คิดว่าการศึกษาของบุคคลนี้จะ เป็นธุรกิจเพียงไม่กี่เดือนและในไม่ช้าพวกเขาควรจะได้ยินเขาให้ข้อสังเกตที่โดดเด่นที่สุดเกี่ยวกับลักษณะชีวิตในอดีตของเขา แทนที่จะเป็นเช่นนี้ พวกเขาเห็นอะไร? - เป็นเด็กขี้เหวี่ยง ขี้เหวี่ยง มีอาการกระตุกและชักบ่อย รักษาสมดุลตัวเองเหมือนสัตว์บางชนิดในสวนสัตว์ กัดและข่วนผู้ที่ต่อต้านเขา ไม่แสดงความรักต่อผู้ที่มาเยี่ยมเยียนเขา และกล่าวโดยย่อคือ ไม่แยแสกับทุกคน และไม่คำนึงถึงสิ่งใดๆ

อาจจินตนาการได้ง่ายว่าสิ่งมีชีวิตในลักษณะนี้จะกระตุ้นความอยากรู้ชั่วขณะเท่านั้น ผู้คนมารวมกันเป็นฝูง พวกเขาเห็นพระองค์โดยไม่ได้สังเกตให้ดี พวกเขาตัดสินเขาโดยที่เขาไม่รู้จัก และไม่พูดในเรื่องนั้นอีก ท่ามกลางความเฉยเมยทั่วไปนี้ ผู้บริหารของสถาบันแห่งชาติเพื่อคนหูหนวกและเป็นใบ้และผู้อำนวยการที่มีชื่อเสียงโด่งดัง อย่าลืมว่าสังคมซึ่งดึงเอาเยาวชนผู้โชคร้ายคนนี้มาสู่ตัวเธอเอง ได้ทำสัญญาผูกมัดต่อภาระหน้าที่ที่ขาดไม่ได้ซึ่งเธอผูกมัดไว้ . เติมเต็ม. เมื่อเข้าสู่ความหวังที่ฉันได้รับจากการรักษาทางการแพทย์ พวกเขาตัดสินใจว่าควรมอบความเท็จให้การดูแลของฉัน

ก่อนที่ข้าพเจ้าจะนำเสนอรายละเอียดและผลลัพธ์ของมาตรการนี้แก่ผู้อ่าน ข้าพเจ้าต้องระบุประเด็นที่เราได้กำหนด ระลึกถึง และอธิบายขั้นตอนแรก เพื่อให้เห็นคุณค่าของความก้าวหน้าที่เราได้ทำไปแล้วได้ดียิ่งขึ้น และโดยการต่อต้านอดีตจนถึงปัจจุบัน เราอาจสามารถยืนยันสิ่งที่คาดหวังในอนาคตได้ดีขึ้น ดังนั้น จำเป็นต้องย้อนกลับไปยังข้อเท็จจริงที่ทราบกันดีอยู่แล้ว ข้าพเจ้าจะเปิดเผยข้อเท็จจริงเหล่านั้นด้วยถ้อยคำไม่กี่คำ และเพื่อที่ข้าพเจ้าจะไม่ทำงานภายใต้ข้อสงสัยว่าได้พูดเกินจริงโดยเพิ่มความสำคัญของสิ่งที่ข้าพเจ้าจะคัดค้าน ข้าพเจ้าอาจได้รับการอภัยหากข้าพเจ้าให้คำอธิบายเชิงวิเคราะห์เกี่ยวกับกรณีซึ่งแพทย์เป็นอย่างสูง ยกย่องในพระอัจฉริยภาพและทักษะในการสังเกต ส่วนความรู้ลึกซึ้งในเรื่องโรคของจิตใจ อ่านให้สังคมแห่งการเรียนรู้ฟัง ซึ่งข้าพเจ้าได้รับเกียรติให้รับเข้าศึกษา

เริ่มต้นด้วยเรื่องราวเกี่ยวกับการทำงานของประสาทสัมผัสของเด็กหนุ่มป่าเถื่อน Citizen Pinel แสดงให้เราเห็นว่าประสาทสัมผัสของเขาอยู่ในสภาวะเฉื่อยชา ตามรายงานของเขาพบว่าเยาวชนที่โชคร้ายนี้ด้อยกว่าสัตว์เลี้ยงของเราบางตัวมาก นัยน์ตาของเขาไม่นิ่ง ไม่แสดงออก เดินจากสิ่งหนึ่งไปยังอีกสิ่งหนึ่งโดยไม่ได้จับจ้องสิ่งใด ได้รับคำแนะนำน้อยมากในด้านอื่น ๆ และมีประสบการณ์น้อยมากในด้านความรู้สึก จนไม่สามารถแยกความแตกต่างระหว่างวัตถุในรูปนูนและภาพวาดได้ อวัยวะของการได้ยินนั้นเหมือนกันจนไม่สามารถรับรู้ถึงเสียงที่ดังที่สุดและเสียงดนตรีที่ไพเราะที่สุดได้ : เสียงนั้นยังไม่สมบูรณ์มากขึ้น พูดเพียงเสียงในลำคอและสม่ำเสมอ: การรับรู้กลิ่นของเขาได้รับการฝึกฝนน้อยมาก จนดูเหมือนเขาไม่สนใจกลิ่นของน้ำหอมที่ดีที่สุดเท่าๆ กัน และการหายใจออกที่น่าขยะแขยงที่สุด ในที่สุด ความรู้สึกของความรู้สึกถูกจำกัดไว้เฉพาะหน้าที่ทางกลไกซึ่งเกิดขึ้นจากความกลัวของวัตถุที่อาจขวางทางเขา

เมื่อพิจารณาถึงสถานะของสติปัญญาของเด็กคนนี้แล้ว ผู้เขียนรายงานได้แสดงให้เขาเห็นแก่เราในฐานะที่ไร้ซึ่งความสนใจ (เว้นแต่จะเคารพในวัตถุที่เขาต้องการ) และเป็นผลจากการทำงานของจิตใจทั้งหมดซึ่งขึ้นอยู่กับมัน ; ขาดความทรงจำ ไม่มีวิจารณญาณ แม้แต่นิสัยชอบเลียนแบบ และความคิด 1ns ที่มีขอบเขตมาก แม้แต่ความคิดที่เกี่ยวข้องกับความต้องการเฉพาะหน้าของเขา การโกหกนั้นไม่สามารถเปิดประตูได้ หรือไม่สามารถลุกบนเก้าอี้เพื่อรับอาหารซึ่งถูกยื่นให้พ้นมือของเขา ; กล่าวโดยย่อคือ หมดสิ้นทุกวิถีทางในการสื่อสาร ไม่แสดงออกหรือตั้งใจกับท่าทางและการเคลื่อนไหวของร่างกายของเขา ผ่านไปอย่างรวดเร็วและไม่มีแรงจูงใจใด ๆ จากสภาวะเศร้าโศกอย่างสุดซึ้งไปจนถึงการระเบิดเสียงหัวเราะที่เกินควรที่สุด ไม่มีความรู้สึกต่อความรักทางศีลธรรมทุกชนิด การแยกแยะของเขาไม่เคยตื่นเต้น แต่ด้วยการกระตุ้นของความตะกละ ความสุขของเขา, ความรู้สึกที่พอใจในอวัยวะแห่งรส; ความเฉลียวฉลาด ความไวต่อการสร้างความคิดที่ไม่ต่อเนื่องกัน ซึ่งเชื่อมโยงกับความต้องการทางร่างกายของเขา กล่าวอีกนัยหนึ่งการดำรงอยู่ทั้งหมดของเขาคือชีวิตสัตว์ล้วน ๆ

หลังจากนั้น ท่องประวัติศาสตร์มากมายที่รวบรวมได้ที่ Bicêtre เกี่ยวกับเด็กที่ได้รับผลกระทบจากความงี่เง่าอย่างต่อเนื่อง Citizen Pinel ได้สร้างความคล้ายคลึงที่โดดเด่นที่สุดระหว่างสถานการณ์ของคนที่โชคร้ายเหล่านี้กับเด็กที่ได้รับความสนใจจากเราในปัจจุบัน จากผลที่จำเป็น เขาดึงเอาตัวตนที่สมบูรณ์แบบระหว่างคนงี่เง่ารุ่นเยาว์เหล่านี้กับ Savage of Aveyron อัตลักษณ์นี้นำไปสู่ข้อสรุปที่หลีกเลี่ยงไม่ได้ว่าบุคคลที่ทำงานภายใต้ความทุกข์ยากซึ่งจนบัดนี้ถือว่ารักษาไม่หาย เป็นคนที่ไม่สามารถเข้าสังคมและสั่งสอนได้ทุกประเภท สิ่งเหล่านี้เป็นผลมาจากการอนุมานโดย Citizen Pinel ซึ่งเขามาพร้อมกับข้อสงสัยทางปรัชญานั้น ซึ่งเห็นได้ชัดเจนในงานเขียนทั้งหมดของเขา และซึ่งแสดงให้เห็นในคำปราศรัยของเขา ว่าเขารู้วิธีที่จะชื่นชมศาสตร์แห่งการพยากรณ์โรค และคำโกหกนั้นถือว่าสิ่งนี้ กรณีที่อนุญาตเฉพาะความน่าจะเป็นและการคาดเดาที่ไม่แน่นอนเท่านั้น

ฉันไม่เห็นด้วยกับความคิดเห็นที่ไม่พึงประสงค์นี้ และแม้จะมีความจริงของภาพและความถูกต้องของการนำเสนอ แต่ฉันก็มีความหวังบางอย่าง ซึ่งมีพื้นฐานมาจากการพิจารณาสองครั้งของสาเหตุและความเป็นไปได้ในการรักษาความงี่เง่าที่เห็นได้ชัดนี้ ฉันไม่สามารถดำเนินการต่อไปได้หากไม่หยุดชั่วขณะเพื่อพิจารณาข้อพิจารณาทั้งสองนี้ พวกเขายังคงทนอยู่กับปัจจุบันขณะ สิ่งเหล่านี้เป็นผลจากชุดของข้อเท็จจริงที่ข้าพเจ้ากำลังจะเล่า และข้าพเจ้าจำเป็นต้องผสมผสานการไตร่ตรองของข้าพเจ้าเองบ่อยๆ

หากจะเสนอเพื่อแก้ไขปัญหาทางอภิปรัชญาดังต่อไปนี้ “เพื่อตัดสินว่าระดับของความเข้าใจจะเป็นเช่นไร และธรรมชาติของความคิดของเยาวชน ผู้ซึ่งถูกกีดกันจากวัยเด็ก การศึกษาทั้งหมดควรมีชีวิตอยู่โดยแยกจากบุคคลในเผ่าพันธุ์ของเขาอย่างสิ้นเชิง” ฉันถูกหลอกอย่างน่าประหลาด มิฉะนั้น วิธีแก้ปัญหาจะให้ความเข้าใจแก่บุคคลนี้ซึ่งเชื่อมโยงกับความต้องการเพียงเล็กน้อยของเขา และถูกลิดรอนโดยสภาพที่หุ้มฉนวนของเขา ความคิดที่เรียบง่ายและซับซ้อนทั้งหมดที่เราได้รับจากการศึกษา และ ซึ่งรวมกันอยู่ในความคิดของเราด้วยวิธีต่างๆ มากมาย โดยอาศัยความรู้จากสัญญาณเท่านั้น ดี! ภาพลักษณ์ทางศีลธรรมของเยาวชนนี้จะเป็นของ Savage of Aveyron และการแก้ปัญหาจะเป็นตัววัดและสาเหตุของสภาวะทางปัญญาของเขา

แต่เพื่อยอมรับด้วยเหตุผลที่มากกว่านั้น การมีอยู่ของสาเหตุนี้ เราต้องพิสูจน์ว่ามันดำเนินมาหลายปีแล้ว และเพื่อตอบข้อโต้แย้งซึ่งอาจมีขึ้นและได้เริ่มต้นไปแล้วจริง ๆ ว่าผู้แสร้งทำเป็นอำมหิต เป็นเพียงเด็กงี่เง่าน่าสงสารที่พ่อแม่ของเขาทิ้งขว้างไว้ที่ทางเข้าป่าด้วยความขยะแขยง — หากผู้ที่ยังคงความเห็นนี้สังเกตเห็นเขาภายในระยะเวลาอันสั้นหลังจากที่เขามาถึงปารีส พวกเขาคงจะสังเกตเห็นว่าทั้งหมด นิสัยของเขาเบื่อชีวิตพเนจรและสันโดษ ความเกลียดชังที่เอาชนะไม่ได้จากสังคมและขนบธรรมเนียมของสังคม จากเสื้อผ้า เฟอร์นิเจอร์ อพาร์ตเมนต์ และวิธีการเตรียมอาหารของเรา ความไม่แยแสต่อวัตถุแห่งความสุขของเราและความต้องการที่เป็นข้อเท็จจริงของเรา - รสนิยมที่เร่าร้อนสำหรับเสรีภาพของท้องทุ่ง รอดพ้นจากสถานการณ์ในอดีตของเขา แม้ว่าเขาจะมีความต้องการใหม่และความรักที่มากขึ้นเรื่อย ๆ จนในช่วงที่เขาพักระยะสั้น ๆ ที่มอนต์โมเรนซี เขาคงจะหนีเข้าไปในป่าอย่างไม่ผิดพลาด แต่ด้วยมาตรการป้องกันที่เข้มงวดที่สุด และสองครั้งที่เขาออกจากโรงพยาบาลคนหูหนวกและเป็นใบ้, ทั้ง ๆ ที่ผู้ดูแลของเขาเฝ้าระวังอยู่; - ความรวดเร็วเป็นพิเศษ ช้า จริง ๆ แล้ว ตราบใดที่เขาสวมรองเท้าและถุงน่อง แต่ก็น่าทึ่งเสมอสำหรับความยากลำบากที่เขาปรับให้เข้ากับโหมดการเดินที่หนักอึ้งและวัดได้ของเรา — นิสัยดื้อรั้นที่จะได้กลิ่นทุกสิ่ง* ที่เข้ามาในทางทวิภาค แม้แต่ร่างกายซึ่งเราดูเหมือนไม่มีกลิ่น การบดเคี้ยวซึ่งน่าประหลาดใจไม่น้อย ดำเนินการอย่างสม่ำเสมอโดยการดำเนินการอย่างเร่งรีบของฟันตัด ซึ่งแสดงให้เห็นอย่างเพียงพอโดยเปรียบเทียบกับสัตว์อื่นๆ บางชนิดว่าคนป่าของเราอาศัยอยู่บนพืชผักเป็นส่วนใหญ่ ข้าพเจ้ากล่าวโดยประการสำคัญเพราะโดยลักษณะต่อไปนี้ ปรากฏว่า ในบางสถานการณ์ การโกหกจะทำให้เหยื่อที่เป็นสัตว์เล็กๆ หมดชีวิต วันหนึ่งนกขมิ้นที่ตายแล้วได้รับนกเขา และในทันใด เขาก็ถอดขนของมันออก ทั้งใหญ่และเล็กใช้เล็บฉีกออก ดมกลิ่นแล้วโยนทิ้งไป

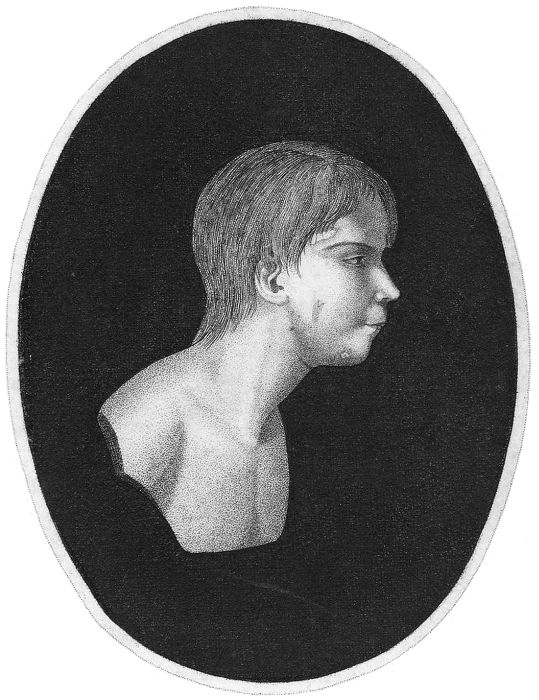

สิ่งบ่งชี้อื่น ๆ เกี่ยวกับชีวิตที่ไม่ปลอดภัย ล่อแหลม และพเนจร อนุมานได้จากลักษณะและจำนวนของแผลเป็นที่ปกคลุมร่างกายของเด็กคนนี้ โดยไม่กล่าวถึงสิ่งที่เห็นที่ส่วนหน้าของคอของเขา ซึ่งฉันจะแจ้งให้ทราบต่อไปว่ามาจากสาเหตุอื่นและสมควรได้รับการเอาใจใส่เป็นพิเศษ เรานับสี่ที่ใบหน้า หกที่แขนซ้าย สามที่ระยะห่างกัน จากไหล่ซ้าย สี่เส้นรอบหัวหน่าว หนึ่งอันบนต้นขาซ้าย สามอันที่ขาข้างหนึ่ง และอีกสองอันที่อีกข้างหนึ่ง ซึ่งรวมกันแล้วทำให้เกิดรอยแผลเป็นถึงยี่สิบสามรอย — บางส่วนดูเหมือนจะมาจากการกัดของสัตว์ บางส่วนมาจากการข่วนและการขูดออก ไม่มากก็น้อยและลึกกว่านั้น ประจักษ์พยานจำนวนมากและลบล้างไม่ได้เกี่ยวกับการละทิ้งเยาวชนที่โชคร้ายคนนี้อย่างยาวนานและสิ้นเชิง ซึ่งเมื่อพิจารณาภายใต้มุมมองทั่วไปและในเชิงปรัชญาแล้ว ก็เป็นประจักษ์พยานมากพอๆ กับความอ่อนแอและความไม่เพียงพอของมนุษย์ โดยมอบให้กับทรัพยากรของเขาเองทั้งหมด ดังเช่น พวกเขาเอื้อประโยชน์ต่อทรัพยากรของธรรมชาติ ซึ่งตามกฎหมายดูเหมือนจะขัดแย้งกัน พวกเขาทำงานอย่างเปิดเผยเพื่อต่ออายุและอนุรักษ์สิ่งที่เธอมักจะแอบทิ้งขยะและทำลาย หากเราเพิ่มข้อเท็จจริงเหล่านี้ซึ่งได้มาจากการสังเกต ซึ่งไม่น้อยไปกว่าความจริงที่คนในชนบทได้พบเห็นซึ่งอาศัยอยู่ใกล้กับป่าที่พบเด็ก เราจะพบว่า เมื่อเขาถูกพาเข้าสู่สังคมครั้งแรก เขา อาศัยอยู่บนลูกโอ๊ก มันฝรั่ง และเกาลัดดิบ ที่เขาไม่เคยโยนเปลือกออก; แม้ว่าจะมีการระแวดระวังอย่างแข็งขันที่สุด เขาก็เกือบหลายครั้งที่จะหลบหนี ที่เขาแสดงความไม่เต็มใจอย่างยิ่งที่จะนอนบนเตียง & ค. ยิ่งกว่านั้น เราจะพบว่าเขาเคยเห็นมาก่อนเมื่อห้าปีก่อน เปลือยกายทั้งตัว และโบยบินเข้าหามนุษย์ ซึ่งสมมุติว่าเขาได้เคยชินกับชีวิตแบบนั้นแล้ว ในครั้งแรกที่ปรากฏตัว ซึ่งไม่อาจเป็นผลจากที่อาศัยเพียงสองปีหรือน้อยกว่านั้นในที่ที่ไม่มีใครอยู่ ดังนั้น เด็กคนนี้จึงผ่านไปเกือบเจ็ดปีจากทั้งหมดสิบสองปีด้วยความสันโดษ ซึ่งดูเหมือนว่าจะเท่ากับอายุของเขาเมื่อเขาถูกจับได้ในป่าแห่งเคาน์ ดังนั้นจึงเป็นไปได้และเกือบจะแน่นอนว่าเขาถูกทอดทิ้งเมื่อเขาอายุประมาณสี่หรือห้าขวบ และถ้าในช่วงเวลานั้น เขาได้รับแนวคิดบางอย่างแล้ว และความรู้ของคำบางคำเมื่อเริ่มต้นการศึกษา สิ่งเหล่านี้จะถูกลบเลือนไปจากความทรงจำของเขา ส่งผลให้สถานการณ์ของเขาถูกปิดกั้น

สิ่งนี้ดูเหมือนจะเป็นสาเหตุของสถานะปัจจุบันของเขาซึ่งจะเห็นว่าฉันมีความหวังอย่างมากสำหรับความสำเร็จของการดูแลของฉัน เมื่อเราพิจารณาถึงเวลาอันน้อยนิดที่เขาอยู่ในสังคม Savage of Aveyron ก็เหมือนเด็กธรรมดาๆ น้อยกว่าทารกอายุสิบหรือสิบสองเดือน และยังเป็นทารกที่ควรมีนิสัยต่อต้านสังคมต่อต้านเขา ดื้อรั้น ไม่ตั้งใจ อวัยวะต่างๆ แทบจะไม่ยืดหยุ่น และสติสัมปชัญญะทื่อมาก ในมุมมองสุดท้ายนี้ สถานการณ์ของเขากลายเป็นกรณีทางการแพทย์ล้วน ๆ และการรักษานั้นเป็นของการแพทย์ทางศีลธรรม - สำหรับงานศิลปะอันสูงส่งนั้นสร้างขึ้นโดย Willis's และ Crichton's ของอังกฤษ และต่อมาได้ถูกนำเข้าสู่ฝรั่งเศสโดยความสำเร็จและงานเขียนของ ศาสตราจารย์ปิเนล

โดยมีจิตวิญญาณแห่งหลักคำสอนของพวกเขานำทางน้อยกว่าหลักคำสอนของพวกเขามาก ซึ่งไม่สามารถปรับให้เข้ากับกรณีที่ไม่คาดฝันนี้ได้ ฉันจึงลดหัวหน้าหลักห้าคนจากการปฏิบัติทางศีลธรรมหรือของ Savage of Aveyron

วัตถุของฉันคือ

การผูกเขาเข้ากับชีวิตทางสังคมโดยการแสดงมันเป็นสิ่งที่น่ายินดีสำหรับเขามากกว่าสิ่งที่เขาเป็นผู้นำในตอนนั้น และเหนือสิ่งอื่นใด คล้ายกับโหมดการดำรงอยู่ที่เขากำลังจะลาออก เพื่อปลุกความรู้สึกทางประสาทโดยตัวกระตุ้นที่มีพลังมากที่สุด และบางครั้งโดยความรู้สึกที่มีชีวิตชีวาของจิตใจ เพื่อขยายขอบเขตความคิดของเขาโดยให้ความต้องการใหม่แก่เขาและเพิ่มจำนวนความสัมพันธ์ของเขากับวัตถุที่อยู่รอบตัวเขา นำเขาไปสู่การใช้คำพูดโดยบังคับให้เขาเลียนแบบ. ในการออกกำลังกายบ่อย ๆ การดำเนินการที่ง่ายที่สุดของจิตใจต่อวัตถุที่ต้องการทางร่างกายของเขา และในที่สุดโดยการชักนำให้นำไปใช้กับวัตถุของคำสั่งสอน ส่วนที่ 1 เป้าหมายแรกของฉันคือผูกเขาไว้กับชีวิตทางสังคม โดยทำให้เขาพอใจมากกว่าที่เขาเป็นผู้นำ และเหนือสิ่งอื่นใด คล้ายกับโหมดการดำรงอยู่ที่เขากำลังจะลาออก

การเปลี่ยนแปลงอย่างกะทันหันในวิถีชีวิตของเขา การรวมตัวกันบ่อยครั้งของผู้อยากรู้อยากเห็น บางคนได้รับการรักษา และผลกระทบที่หลีกเลี่ยงไม่ได้จากการอยู่ร่วมกับเด็กรุ่นราวคราวเดียวกันดูเหมือนจะทำให้ความหวังทั้งหมดที่มีต่ออารยธรรมของเขาดับวูบลง กิจกรรมทางจิตใจที่ขี้งอนของเขาได้เสื่อมลงอย่างไร้เหตุผลจนกลายเป็นความไม่แยแสที่น่าเบื่อ ซึ่งทำให้เกิดนิสัยที่ยังคงโดดเดี่ยวมากขึ้น ดังนั้น ยกเว้นช่วงเวลาที่ความหิวพาเขาไปที่ห้องครัว เขามักจะนั่งยองๆ อยู่ที่มุมสวนหรือซ่อนตัวอยู่ในชั้นสองของอาคารที่พังทลาย ในสถานการณ์ที่น่าสลดใจนี้ คนบางคนจากปารีสเห็นการโกหก ซึ่งหลังจากการตรวจสอบไม่นานนัก ตัดสินให้เขาถูกจุดไฟเพื่อส่งไปยังเบดแลมเท่านั้น ราวกับว่าสังคมมีสิทธิที่จะพรากเด็กคนหนึ่งไปจากชีวิตที่เป็นอิสระและไร้เดียงสา และปล่อยให้เขาตายอย่างเศร้าโศกในบ้านคนบ้า เพื่อที่เขาจะได้ลบล้างความโชคร้ายของความอยากรู้อยากเห็นของสาธารณชนที่ผิดหวัง ฉันคิดว่าแนวทางที่เรียบง่ายกว่านี้และที่สำคัญยิ่งกว่านั้น ควรใช้แนวทางที่มีมนุษยธรรมมากกว่านี้ ซึ่งก็คือการปฏิบัติต่อเขาด้วยความกรุณาและยอมทำตามรสนิยมและความโน้มเอียงของเขา มาดามเกริน ซึ่งฝ่ายบริหารได้มอบความไว้วางใจให้กับเด็กคนนี้ดูแลเป็นพิเศษ พ้นผิดแล้ว และยังคงทำงานอันยากลำบากนี้ด้วยความอดทนทั้งหมดของผู้เป็นแม่ และความเฉลียวฉลาดของผู้สอนที่รู้แจ้ง ห่างไกลจากการต่อต้านนิสัยของเขาโดยตรง เธอรู้วิธีที่จะปฏิบัติตามนิสัยเหล่านี้ในระดับหนึ่ง และด้วยเหตุนี้จึงตอบเป้าหมายที่เสนอในหัวหน้าทั่วไปคนแรกของเรา

ถ้าใครจะตัดสินชีวิตในอดีตของเด็กคนนี้ด้วยอุปนิสัยในปัจจุบัน เราอาจสรุปได้ว่า เฉกเช่นคนป่าเถื่อนบางคนในสภาพอากาศที่ร้อนกว่า เขาคุ้นเคยกับสถานการณ์เพียงสี่ประการเท่านั้น จะนอนจะกินไม่ทำอะไรเลยและวิ่งเล่นในทุ่งนา เพื่อให้เขามีความสุขตามมารยาทของเขา จำเป็นต้องพาเขาเข้านอนในตอนใกล้วัน จัดหาอาหารมากมายให้เขาตามรสนิยมของเขา อดทนต่อความเกียจคร้านของเขา และไปกับเขา เดินหรือมากกว่าในการแข่งของเขาในที่โล่งและเมื่อใดก็ตามที่เขาต้องการ การทัศนศึกษาในชนบทเหล่านี้ดูน่าพอใจยิ่งขึ้นเมื่อมีการเปลี่ยนแปลงอย่างกะทันหันและรุนแรงในบรรยากาศ จริงอยู่ว่าในทุกสภาวะ มนุษย์ยินดีกับความรู้สึกใหม่ๆ ตัวอย่างเช่น เมื่อเขาถูกสังเกต ภายในห้องของเขา เขาเห็นการทรงตัวด้วยเครื่องแบบที่น่าเบื่อหน่าย เพ่งสายตาไปที่หน้าต่างตลอดเวลา และทอดสายตาไปยังอากาศภายนอกด้วยท่าทีเศร้าโศก ถ้าคราวใดเกิดลมกรรโชกขึ้น หากดวงอาทิตย์ที่ซ่อนอยู่หลังก้อนเมฆ จู่ๆ ก็โผล่ออกมา ส่องสว่างแก่บรรยากาศรอบข้าง เขาแสดงความดีใจจนแทบชักกระตุกด้วยเสียงหัวเราะดังลั่น ในระหว่างนั้น ทุกสิ่งก็พลิกผัน ถอยหลังไปข้างหน้า คล้ายกับการกระโดดแบบหนึ่งซึ่งเขาอยากจะกระโดดออกไปนอกหน้าต่างเข้าไปในสวน บางครั้ง แทนที่จะแสดงอารมณ์สนุกสนาน เขาแสดงความบ้าคลั่ง เขาบิดมือ ใช้กำปั้นขยี้ตา กัดฟัน และกลายเป็นคนที่น่าเกรงขามต่อผู้คนรอบตัวเขา เช้าวันหนึ่ง หลังจากหิมะตกหนัก ทันทีที่เขาตื่นขึ้น เขาก็เปล่งเสียงร้องด้วยความดีใจ กระโดดลงจากเตียง วิ่งไปที่หน้าต่าง แล้วไปที่ประตู ถอยหลังไปข้างหน้า จากที่หนึ่งไปอีกที่หนึ่ง พร้อมกับ ความใจร้อนที่ยิ่งใหญ่ที่สุดและท้ายที่สุดก็หลบหนีเข้าไปในสวน ที่นั่นเขาแสดงอารมณ์แห่งความสุขอย่างเต็มที่ เขาวิ่ง กลิ้งตัวไปบนหิมะ และหยิบมันขึ้นมา กลืนกินมันด้วยความทะเยอทะยานอย่างไม่น่าเชื่อ

แต่เขาไม่ได้แสดงออกถึงความสุขที่มีชีวิตชีวาและอึกทึกเช่นนี้เสมอไปเมื่อได้เห็นปรากฏการณ์อันยิ่งใหญ่ของธรรมชาติ ในบางกรณี ดูเหมือนว่าพวกเขาจะกระตุ้นให้แสดงความเศร้าโศกและเศร้าโศกอย่างเงียบๆ คำพูดที่เป็นอันตรายต่อความคิดเห็นของนักอภิปรัชญา แต่เราไม่สามารถหลีกเลี่ยงได้เมื่อเราสังเกตเยาวชนที่โชคร้ายคนนี้ด้วยความสนใจภายใต้การดำเนินการของสถานการณ์บางอย่าง A\ Lien ความรุนแรงของฤดูกาลทำให้ทุกคนออกจากสวน เขารู้สึกยินดีที่ได้ผลัดเปลี่ยนกันมากมายเกี่ยวกับเรื่องนี้ ครั้นแล้วก็นอนเอนกายลงที่ขอบแอ่งน้ำ ฉันมักจะลาดเลาเป็นเวลาหลายชั่วโมงด้วยกันและด้วยความยินดีอย่างสุดจะพรรณนาเพื่อตรวจสอบเขาในสถานการณ์นี้ เพื่อสังเกตว่าการเคลื่อนไหวที่ชักกระตุกทั้งหมดของเขาและการทรงตัวอย่างต่อเนื่องของร่างกายทั้งหมดของเขาลดลงและค่อยๆ ลดลง เพื่อให้มีทัศนคติที่สงบมากขึ้น และพระพักตร์ของพระองค์ดูจืดชืดหรือบิดเบี้ยวอย่างไร้ความรู้สึกเพียงใด ปรากฏลักษณะของความโศกเศร้าหรือภวังค์อันเศร้าหมองอย่างชัดเจน ในสัดส่วนที่พระเนตรจับจ้องที่ผิวน้ำอย่างมั่นคง และเมื่อเขากระโจนลงไปในน้ำ บางคราวก็เหลือแต่ใบไม้เหี่ยวๆ เมื่อในคืนแสงจันทร์ แสงของดวงไฟนั้นส่องเข้ามาในห้องของเขา เขาไม่ค่อยจะตื่นจากการหลับใหลและวางตัวเองไว้หน้าหน้าต่าง เขายังคงอยู่ ณ ที่แห่งนั้น ในช่วงเวลาหนึ่งของคืน ยืนนิ่งไม่ขยับ คอของเขายื่นออก สายตาของเขาจับจ้องไปยังดินแดนที่ส่องสว่างด้วยดวงจันทร์ และดำเนินไปด้วยความปีติยินดีแบบครุ่นคิด ความเงียบงันถูกขัดจังหวะโดยส่วนลึกเท่านั้น- ได้รับการดลใจ เปลี่ยนช่วงเวลามากมาย และมักจะมาพร้อมกับเสียงที่อ่อนแอและคร่ำครวญ

มันคงไร้ประโยชน์พอๆ กับไร้มนุษยธรรมที่จะต่อต้านนิสัยเหล่านี้ และฉันก็อยากจะเชื่อมโยงมันเข้ากับการมีอยู่ใหม่ของเขา เพื่อให้มันเข้ากับเขามากขึ้น นี่ไม่ใช่กรณีของผู้ที่ตรากตรำทำงานภายใต้ความเสียเปรียบของการออกกำลังกายหน้าท้องและกล้ามเนื้ออย่างต่อเนื่อง และแน่นอนว่าปล่อยให้อยู่ในสภาพเฉื่อยชา ประสาทสัมผัส และการทำงานของสมอง ดังนั้น ฉันจึงพยายามและค่อยๆ ประสบความสำเร็จในความพยายามที่จะทำให้เขาไปเที่ยวน้อยลง อาหารของเขามากมายน้อยลง และทำซ้ำหลังจากเว้นช่วงนานขึ้น เวลาที่เขาใช้บนเตียงสั้นลงมาก และการออกกำลังกายของเขาเป็นไปตามคำสั่งของเขามากขึ้น เป้าหมายที่สองของฉันคือการปลุกความรู้สึกทางประสาทด้วยสารกระตุ้นที่ทรงพลังที่สุด และบางครั้งด้วยความรู้สึกที่มีชีวิตชีวาของจิตใจ

นักสรีรวิทยาสมัยใหม่บางคนสันนิษฐานว่าความรู้สึกนั้นเป็นสัดส่วนที่แน่นอนกับระดับของอารยธรรม ฉันสงสัยว่าจะสามารถให้ข้อพิสูจน์ที่หนักแน่นกว่านี้เพื่อสนับสนุนความคิดเห็นนี้ได้ดีกว่าระดับความรู้สึกเล็กน้อยในอวัยวะรับสัมผัสซึ่งสังเกตได้ในกรณีของ Savage of Aveyron เราอาจพึงพอใจอย่างยิ่ง เพียงแค่ละสายตาจากคำอธิบายที่ฉันได้แสดงไปแล้ว ซึ่งตั้งอยู่บนข้อเท็จจริงที่ฉันได้มาจากแหล่งที่แท้จริงที่สุด ฉันจะเพิ่มที่นี่ในส่วนที่เกี่ยวข้องกับเรื่องเดียวกัน ข้อสังเกตที่น่าสนใจและสำคัญที่สุดของฉันเอง

บ่อย ๆ ในฤดูหนาว ข้าพเจ้าได้เห็นเขาขณะกำลังนอนขบขันอยู่ในสวนของสถานสงเคราะห์คนหูหนวกเป็นใบ้ ทันใดนั้นหมอบลง เปลือยครึ่งท่อน บนสนามหญ้าเปียก และยังคงเปิดเผยในลักษณะนี้ เพราะ ชั่วโมงกันทั้งลมและฝน ไม่ใช่แค่ความหนาวเย็นเท่านั้น แต่ยังรวมถึงความร้อนที่รุนแรงที่สุดด้วย ซึ่งผิวหนังและความรู้สึกสัมผัสของเขาไม่แสดงความรู้สึกใดๆ เลย เกิดขึ้นบ่อยครั้ง เมื่อพระองค์อยู่ใกล้ไฟ และถ่านที่ยังคุกรุ่นหลุดออกจากตะแกรง พระองค์ก็ทรงฉวยมันขึ้นมา แล้วโยนกลับไปอีกครั้งด้วยความเฉยเมยอันหาที่สุดมิได้ เราพบเขามากกว่าหนึ่งครั้งในครัว เอามันฝรั่งออกจากน้ำเดือดในลักษณะเดียวกัน และฉันรู้ว่าในเวลานั้นเขามีผิวที่มีเนื้อละเอียดและละเอียดอ่อนมาก *

- ฉันให้มันฝรั่งจำนวนมากแก่เขาซึ่งเคยเห็นเขาที่ St. Sernin; ดูเหมือนว่าพระองค์จะพอพระทัยในสายตานั้น จับมือพวกเขาแล้วโยนเข้าไปในกองไฟ หลังจากนั้นไม่นาน เขาก็นำมันกลับมาอีก และกินมันอย่างร้อนจัด

ฉันมักจะให้เขาดมปริมาณมากโดยไม่มีท่าทางตื่นเต้นที่จะจาม ซึ่งเป็นข้อพิสูจน์ที่สมบูรณ์ว่า ในกรณีนี้ ไม่มีระหว่างอวัยวะรับกลิ่นกับอวัยวะรับกลิ่นและการมองเห็น ความเห็นอกเห็นใจชนิดที่มักจะทำให้จามหรือน้ำตาไหล อาการสุดท้ายนี้ยังคงมีความรับผิดชอบน้อยกว่าอาการอื่นที่เกิดจากความเจ็บปวดทางจิตใจ และแม้จะมีความขัดแย้งนับไม่ถ้วน แม้จะมีการใช้มาตรการที่รุนแรงและดูโหดร้าย โดยเฉพาะอย่างยิ่งในช่วงเดือนแรกของชีวิตใหม่ของเขา ฉันก็ไม่เคยจับเขาร้องไห้เลยสักครั้ง

จากประสาทสัมผัสทั้งหมดของเขา รถของเขาดูเหมือนจะไร้ความรู้สึกที่สุด แต่ที่น่าทึ่งคือเสียงที่เกิดจากการแตกร้าว วอลนัตซึ่งเป็นผลไม้ที่เขาชอบเป็นพิเศษ ปลุกความสนใจของเขาไม่เคยพลาด ความจริงของข้อสังเกตนี้อาจขึ้นอยู่กับ: แต่ถึงกระนั้น อวัยวะส่วนนี้กลับทรยศต่อการไม่รับรู้ต่อเสียงที่ดังที่สุด ต่อเสียงระเบิด เช่น เสียงปืน วันหนึ่งฉันยิงปืนสั้นสองกระบอกใกล้หูเขา คนแรกสร้างอารมณ์บางอย่าง แต่ครั้งที่สองทำให้เขาหันศีรษะด้วยความเฉยเมยอย่างเห็นได้ชัด

ดังนั้น ในการเลือกบางกรณีเช่นนี้ซึ่งความบกพร่องของความสนใจสำหรับจิตใจอาจดูเหมือนต้องการความรู้สึกในอวัยวะนั้น ๆ ตรงกันข้ามกับที่ปรากฏครั้งแรกพบว่าพลังประสาทนี้อ่อนแออย่างน่าทึ่งใน ประสาทสัมผัสเกือบทั้งหมด แน่นอน มันเป็นส่วนหนึ่งของแผนการของฉันที่จะพัฒนาความรู้สึกสัมผัสด้วยทุกวิถีทางที่เป็นไปได้ และนำจิตใจไปสู่นิสัยของความสนใจ โดยเปิดเผยประสาทสัมผัสเพื่อรับความประทับใจที่มีชีวิตชีวาที่สุด

จากวิธีการต่างๆ ที่ฉันใช้ ผลของความร้อนดูเหมือนจะทำให้ฉันบรรลุผลสำเร็จในลักษณะที่มีประสิทธิผลมากที่สุดต่อวัตถุที่ฉันมองเห็น เป็นแนวคิดที่นักสรีรวิทยา*, Lacus ยอมรับ Idea de l'homme ร่างกายและศีลธรรม

- Laroche : วิเคราะห์ des fonctions du system encriveux และผู้ชายที่เรียนมาทางรัฐศาสตร์ ว่าชาวเมืองทางใต้เป็นหนี้บุญคุณต่อการกระทำของความร้อนบนผิว สำหรับความรู้สึกที่ประณีตซึ่งเหนือกว่าพวกเขาที่อาศัยอยู่ใน ภาคเหนือ ฉันใช้ประโยชน์จากสิ่งเร้านี้ในทุกวิถีทาง ฉันไม่คิดว่ามันเพียงพอสำหรับการจัดหาชุดโต๊ะคอม เตียงอุ่นๆ และที่พักให้ แต่ฉันคิดว่าจำเป็นต้องให้เขาแช่ในอ่างน้ำร้อนเป็นเวลาสองหรือสามชั่วโมงทุกวัน ระหว่างนั้นให้ดื่มน้ำ ที่อุณหภูมิเดียวกับน้ำในอ่างถูกฟาดลงบนศีรษะของเขาบ่อยครั้ง ฉันสังเกตเห็นว่าความร้อนและการอาบน้ำซ้ำๆ ตามมาด้วยผลที่ทำให้ร่างกายทรุดโทรมตามปกติ ซึ่งอาจเป็นไปตามที่คาดไว้ ฉันหวังว่าสิ่งนี้อาจเกิดขึ้น โดยเชื่อมั่นอย่างสมบูรณ์ว่า ในกรณีเช่นนี้ การสูญเสียกำลังของกล้ามเนื้อจะเป็นประโยชน์ต่อความรู้สึกทางประสาท

- Fouqun: บทความ Sensibilité de l’Encyclopedie par ordre alphabétique.

- มองเตสกิเออ : Esprit des Lois, livre XIV.

ยังไงก็ตาม ถ้าผลที่ตามมานี้ไม่เกิดขึ้น ผลแรกก็ไม่ทำให้ความคาดหวังของฉันผิดหวัง หลังจากนั้นครู่หนึ่ง ชายหนุ่มผู้อำมหิตของเราดูเหมือนจะสัมผัสได้ถึงความหนาวเย็นอย่างเห็นได้ชัด เขาใช้มือของเขาเพื่อตรวจสอบอุณหภูมิของอ่างน้ำ และจะไม่ลงไปในอ่างหากไม่อุ่นเพียงพอ สาเหตุเดียวกันนี้ทำให้เขาเห็นคุณค่าประโยชน์ของเสื้อผ้าตัวนั้นในไม่ช้า ซึ่งก่อนหน้านี้เขาแทบไม่ได้หยิบยื่นให้เลย ทันทีที่เขาดูเหมือนจะรับรู้ถึงข้อดีของเสื้อผ้า มีกระท่อมเพียงขั้นตอนเดียวที่จำเป็นในการบังคับเขาให้แต่งตัวด้วยตัวเอง จุดจบนี้เกิดขึ้นได้ภายในเวลาไม่กี่วัน โดยปล่อยให้เขาสัมผัสความหนาวเย็นทุกเช้าในระยะที่เสื้อผ้าเอื้อมถึง จนกว่าเขาจะค้นพบวิธีการสวมมันด้วยตัวเอง ประโยชน์ที่คล้ายคลึงกันมากทำให้เกิดความมุ่งหมายในการทำให้เขามีนิสัยเรียบร้อยและสะอาด เนื่องจากความแน่นอนของการผ่านคืนบนเตียงที่เย็นและเปียกชื้นทำให้เขาจำเป็นต้องลุกขึ้นเพื่อสนองความต้องการตามธรรมชาติของเขา

นอกจากการใช้เครื่องอุ่นแล้ว ฉันได้กำหนดการใช้แรงเสียดทานแบบแห้งกับกระดูกสันหลังและแม้แต่การจั๊กจี้บริเวณบั้นเอว วิธีสุดท้ายนี้ดูเหมือนจะมีแนวโน้มกระตุ้นมากที่สุด: ฉันพบว่าตัวเองอยู่ภายใต้ความจำเป็นในการห้ามใช้มันเมื่อผลของมันไม่ จำกัด อยู่ที่การผลิตอารมณ์ที่น่าพึงพอใจอีกต่อไป แต่ดูเหมือนจะขยายตัวเองไปยังอวัยวะของรุ่นและเพื่อบ่งบอก อันตรายบางอย่างในการปลุกความรู้สึกของวัยแรกรุ่นก่อนวัยอันควร สำหรับสารกระตุ้นต่างๆ เหล่านี้ ฉันคิดว่ามันเหมาะสมแล้วที่จะขอความช่วยเหลือจากความตื่นเต้นที่เกิดจากความรู้สึกทางใจ คนที่เขาอ่อนแอเพียงคนเดียวในช่วงเวลานี้ถูกกักขังไว้สองคน ความสุขและความโกรธ ข้าพเจ้ายั่วยุอย่างหลัง ในระยะที่ห่างไกลเท่านั้น เพื่อที่ว่าอาการหวาดระแวงอาจรุนแรงขึ้น และมักจะเข้าร่วมด้วยท่าทางที่สมเหตุสมผลของความยุติธรรม บางครั้งข้าพเจ้าตั้งข้อสังเกตว่า ในช่วงเวลาที่เขาขุ่นเคืองใจอย่างรุนแรงที่สุด ความเข้าใจของเขาดูเหมือนจะขยายใหญ่ขึ้นชั่วคราว ซึ่งเสนอแนะทางอันแยบยลบางอย่างแก่เขาในการปลดเปลื้องตัวเองจากความลำบากใจที่ไม่น่ายินดี ครั้งหนึ่งขณะที่เราพยายามเกลี้ยกล่อมให้เขาใช้อ่างอาบน้ำ ขณะที่มันอุ่นพอประมาณ การขอร้องซ้ำๆ และเร่งด่วนของเราทำให้เขาหลงใหลอย่างรุนแรง ด้วยอารมณ์เช่นนี้ เมื่อเห็นว่าการปกครองของเขาไม่น่าเชื่อถือเลย ด้วยการทดลองบ่อยครั้งซึ่งเขาใช้นิ้วสัมผัสด้วยตัวเองเกี่ยวกับความเย็นของน้ำ เขาจึงหันกลับมาหาเธอในลักษณะที่เร่งรัด จับมือเธอแล้วกระโดดลงไป มันลงอ่างด้วยตัวมันเอง พูดถึงอีกกรณีหนึ่งในลักษณะนี้: วันหนึ่งขณะที่เขานั่งอยู่บนเก้าอี้ออตโตมันในห้องเรียนของฉัน ฉันวางตัวเองไว้ข้างๆ เขา และระหว่างเรามี Leyden phial ซึ่งตั้งข้อหาเล็กน้อย ความตกใจเล็กน้อยที่เขาได้รับจากมันทำให้เขาหันเหจากภวังค์ เมื่อสังเกตเห็นความไม่สบายใจที่เขาแสดงออกเมื่อเข้าใกล้เครื่องมือนี้ ฉันคิดว่าเขาจะถูกชักจูงให้จับลูกบิดเพื่อเอามันออกไปให้ไกลขึ้น เขาใช้มาตรการที่รอบคอบกว่ามาก นั่นคือ สอดมือเข้าไปในช่องเปิดของเสื้อโค้ท และถอยออกมาสองสามนิ้ว จนกระทั่งต้นขาของเขาไม่สัมผัสกับชั้นเคลือบด้านนอกของขวดอีกต่อไป ฉันเข้าไปใกล้เขาเป็นครั้งที่สอง และวางฟีลไว้ระหว่างเราอีกครั้ง สิ่งนี้ทำให้เกิดการเคลื่อนไหวอีกครั้งในส่วนของเขาและอีกอย่างสำหรับฉัน อุบายเล็ก ๆ น้อย ๆ นี้กินเวลาจนกระทั่งถูกผลักไปที่ปลายสุดของโซฟา และถูกจำกัดโดยผนังด้านหลัง ก่อนที่โต๊ะ และด้านข้างของฉันโดยเครื่องจักรที่มีปัญหา มันเป็นไปไม่ได้ที่เขาจะเคลื่อนไหวอีก จากนั้นเขาก็ฉวยจังหวะที่ฉันกำลังยื่นแขนไปจับเขา แล้ววางข้อมือของฉันลงบนลูกบิดโถอย่างคล่องแคล่ว แน่นอนว่าฉันได้รับการปลดประจำการแทนเขา

แต่ถ้าเมื่อไรก็ตาม แม้ว่าฉันจะสนใจและรักเด็กกำพร้าคนนี้อย่างมีชีวิตชีวา แต่ฉันคิดว่ามันเหมาะสมที่จะปลุกความโกรธของเขา ฉันไม่ปล่อยให้โอกาสเดียวที่จะหนีจากฉันไปให้เขาเพลิดเพลิน และมัน และจะต้องเป็น สารภาพว่า เพื่อให้ประสบความสำเร็จในเรื่องนี้ ไม่มีความจำเป็นต้องขอความช่วยเหลือด้วยวิธีใด ๆ ที่เข้าร่วมด้วยความยากลำบากหรือค่าใช้จ่าย ลำแสงของดวงอาทิตย์ รับกระจก สะท้อนในห้องของเขา และโยนขึ้นไปบนเพดาน แก้วน้ำซึ่งถูกทำให้ตกลงมาทีละหยดจากความสูงระดับหนึ่งบนปลายนิ้วมือของเขาในขณะที่เขากำลังอาบน้ำ และแม้กระทั่งน้ำนมเล็กน้อยซึ่งบรรจุอยู่ในหม้อไม้ซึ่งวางไว้ที่ปลายสุดของอ่างของเขา และซึ่งการสั่นไหวของน้ำก็เคลื่อนไหว ทำให้เขาตื่นเต้นในอารมณ์แห่งความสุขที่มีชีวิตชีวา ซึ่งแสดงออกมาด้วยเสียงโห่ร้องและเสียงปรบมือของ มือของเขา: สิ่งเหล่านี้เป็นวิธีการเกือบทั้งหมดที่จำเป็นในการทำให้มีชีวิตชีวาและมีความสุข มักจะเกือบทำให้มึนเมา เด็กธรรมดาๆ ในธรรมชาติคนนี้

สิ่งดังกล่าวคือตัวกระตุ้นรวมทั้งทางร่างกายและทางศีลธรรมซึ่งฉันทำงานเพื่อพัฒนาความรู้สึกสัมผัสของอวัยวะของเขา วิธีการเหล่านี้เกิดขึ้นหลังจากช่วงเวลาสั้น ๆ สามเดือน ความตื่นเต้นทั่วไปของพลังที่ละเอียดอ่อนทั้งหมดของเขา เพราะเวลานั้น สัมผัสนั้นแสดงความรู้สึกสัมผัสของร่างกายได้ทั้งหมด ไม่ว่าจะร้อนหรือเย็น เรียบหรือหยาบ นุ่มหรือแข็ง ในช่วงเวลานั้น ฉันสวมกางเกงชั้นในกำมะหยี่ ซึ่งดูเหมือนเขาจะชอบใจในการดึงมือของเขา โดยการสัมผัสของเขาทำให้เขาแน่ใจว่ามันฝรั่งของเขาต้มเพียงพอหรือไม่: เขาหยิบมันขึ้นมาจากก้นหม้อด้วยช้อน จากนั้นเขาก็ใช้นิ้วจับมันซ้ำๆ แล้วตัดสินใจจากระดับความแข็งหรืออ่อนว่าจะกินหรือจะโยนกลับลงไปในน้ำเดือด เมื่อยื่นกระดาษให้เขาเพื่อจุดเทียน เขาไม่ค่อยรอจนกระทั่งไส้ตะเกียงติดไฟ แต่รีบโยนกระดาษทิ้งก่อนที่เปลวไฟจะใกล้จะสัมผัสนิ้วของเขา หลังจากถูกชักจูงให้ผลักหรือแบกร่างกายที่แข็งหรือหนัก จู่ๆ เขาก็แทบจะไม่ยอมชักมือออก มองดูปลายนิ้วมืออย่างตั้งอกตั้งใจ แม้ว่านิ้วจะไม่ฟกช้ำหรือช้ำเลยแม้แต่น้อย ได้รับบาดเจ็บและวางไว้ในลักษณะสบาย ๆ ในการเปิดเสื้อกั๊กของเขา ประสาทสัมผัสในการดมกลิ่นได้รับการปรับปรุงในทำนองเดียวกัน อันเป็นผลมาจากการเปลี่ยนแปลงที่เกิดขึ้นในร่างของเขา การระคายเคืองน้อยที่สุดที่ใช้กับอวัยวะนี้ ตื่นเต้น จาม; และจากความสยดสยองที่เขาถูกจับในครั้งแรกที่สิ่งนี้เกิดขึ้น ฉันคิดว่ามันเป็นเรื่องใหม่สำหรับเขาโดยสิ้นเชิง เขาตื่นเต้นมากจนแทบจะทิ้งตัวลงบนเตียง

การปรับปรุงการรับรู้รสชาติยังคงโดดเด่นยิ่งขึ้น สิ่งของเกี่ยวกับอาหารที่เด็กคนนี้ได้รับกินหลังจากมาถึงปารีสได้ไม่นานก็น่าขยะแขยงอย่างน่าตกใจ เขาติดตามพวกเขาไปทั่วห้อง และกินมันจากมือของเขาที่เปรอะเปื้อนไปด้วยสิ่งสกปรก แต่ในช่วงเวลาที่ฉันกำลังพูดอยู่นี้ นอนโยนของในจานของเขาทิ้งตลอดเวลา ถ้ามีเศษดินหรือฝุ่นตกลงบนสัตว์เลี้ยง และหลังจากที่เขาหักวอลนัทของเขาแล้ว เขาก็ใช้ความอุตสาหะในการทำความสะอาดมันด้วยวิธีที่ประณีตและละเอียดอ่อนที่สุด

ที่โรคภัยไข้เจ็บ แม้แต่โรคที่เป็นผลที่หลีกเลี่ยงไม่ได้และน่าลำบากใจซึ่งเกิดจากสภาวะของอารยธรรมก็เพิ่มประจักษ์พยานของพวกเขาในการพัฒนาหลักธรรมแห่งชีวิต ในช่วงต้นฤดูใบไม้ผลิ เด็กดุร้ายของเราได้รับผลกระทบจากความหนาวเย็นอย่างรุนแรง และไม่กี่สัปดาห์หลังจากนั้น การโจมตีสองครั้งในลักษณะเดียวกัน การโจมตีหนึ่งครั้งเกือบจะสำเร็จในทันที

อย่างไรก็ตามอาการเหล่านี้จำกัดอยู่เฉพาะในอวัยวะบางส่วนเท่านั้น สายตาและการได้ยินเหล่านั้นไม่ได้รับผลกระทบจากพวกมันเลย เห็นได้ชัดว่าเพราะประสาทสัมผัสทั้งสองนี้ ซึ่งเรียบง่ายกว่าส่วนอื่นๆ มาก ต้องใช้เวลาหนึ่งนาทีและการศึกษาที่ยืดเยื้อมากขึ้น ดังที่จะปรากฏในภาคต่อของประวัติศาสตร์นี้ การปรับปรุงประสาทสัมผัสทั้ง 3 ที่เกิดขึ้นพร้อมกันซึ่งเป็นผลมาจากสารกระตุ้นที่ใช้กับผิวหนัง ในเวลาเดียวกันที่ประสาทสัมผัสทั้งสองยังคงอยู่นิ่ง เป็นข้อเท็จจริงที่สำคัญและสมควรได้รับความสนใจเป็นพิเศษจากนักสรีรวิทยา ดูเหมือนว่าจะพิสูจน์ได้ว่าสิ่งที่ปรากฏจากแหล่งอื่นไม่น่าจะเป็นไปได้ว่าความรู้สึกสัมผัสกลิ่นและรสเป็นเพียงการดัดแปลงอวัยวะของผิวหนังที่แตกต่างกัน ในขณะที่ส่วนหูและตา ซึ่งไม่ได้รับการสัมผัสจากภายนอกน้อยกว่า และถูกห่อหุ้มด้วยสิ่งปกคลุมที่ซับซ้อนกว่ามาก อยู่ภายใต้กฎแห่งการปรับปรุงแก้ไขอื่นๆ และในบัญชีนั้น ควรได้รับการพิจารณาว่าเป็นประเภทที่แตกต่างกันโดยสิ้นเชิง

Section 3

My third object was to extend the sphere of his ideas, by giving him new wants, and multiplying his relations and connections with surrounding objects. If the progress of this child towards civilization; if my success in developing his intelligence has been hitherto so slow and difficult, it ought to be attributed to the almost innumerable obstacles which I have had to encounter in accomplishing this third object. I have given him successively toys of every sort; more than once, for whole hours, I have endeavored to make him acquainted with the use of them, and I have had the mortification cation to observe, that, so far from interesting his attention, these various objects only tended to excite fretfulness and impatience; so much so, that he was continually endeavoring to conceal or destroy them when a favorable opportunity occurred. As an instance of this disposition, after having been some time confined in his chair, with nine-pins placed before him, in order to amuse him in that situation; in consequence of being irritated by this kind of restraint that was imposed upon him, he took it into his head, one day, as he was alone in the chamber, to throw them into the fire; before the flames of which he was immediately after found warming himself, with an expression of great delight.

However, I invented some means of attaching him to certain amusements, which were connected with his appetite for food. One, for instance, I often procured him, at the end of a meal, when I took him to dine with me in the city. I placed before him, without any regular order, and in an inverted position, several little silver goblets, under one of which I put a chestnut. Being: convinced of having; attracted his attention, I raised them, one after another, with the exception of that only which enclosed the chestnut. After having thus proved to him that they contained nothing, and have replaced them in the same order, I invited him, by signs, to seek in his turn for the chestnut; the first goblet on which he cast his e} r es was precisely that under which I had concealed the little recompense of his attention. This was only a very simple effort of memory: but by degrees, I rendered the amusement more complicated. After having, by the same process, concealed another chestnut, I changed the order of all the goblets, in a manner, however, rather slow, in order that, in this general inversion, it might be less difficult for him to follow with his eyes, and with attention, that particular one which concealed the precious deposit. I did more; I put something under three of these goblets, and yet his attention, although divided between three objects, did not fail to pursue them in all the changes of their situation. This is not all; — this was not the only object 1 intended to obtain. The discernment which he exhibited, in this instance, was excited merely by the instinct of gluttony. In order to render his attention less interested, and to a certain degree less animal, I deducted from this amusement everything which had any connection with his palate, and I afterward put nothing under the goblets that were eatable. The result of this experiment was very nearly as satisfactory as the former; and this stratagem afforded nothing* more than a simple amusement: it was not, however, without being of considerable use, in exciting the exercise of his judgment, and inducing a habit of fixed attention.

With the exception of these sorts of diversion, which, like those that have been already mentioned, were intimately connected with his physical wants, it has been impossible for me to inspire him with a taste for those which are natural to his age. I am absolutely certain, that, if I could have effected this, I should have derived from it unspeakable assistance. In order to be convinced of the justness of this idea, we need only attend to the powerful influence which is produced upon the first developments of the mind, by the plays of infancy, as well as the various little pleasures of the palate.

I did every thins; in order to awaken these last inclinations, by offering him those dainties which are most coveted by children, and from which I hoped to derive important advantage; as they afforded me new means of reward; of punishment, of encouragement, and of instruction. But the aversion he expressed for all sweetmeats, and the most tender and delicate viands, was insurmountable. I then thought it right to try the use of highly-stimulating food, as better adapted to excite a sense which was necessarily blunted by the habit of feeding upon grosser aliments. I did not succeed better in this trial; I offered to him, in vain, even during those moments when he felt the most extreme hunger and thirst, strong liquors, and dishes richly seasoned with all kinds of spices. At length, despairing of being able to inspire him with any new taste, I made the most of the small number of those to which his appetite was confined, by endeavoring to accompany them with all the necessary circumstances which might increase the pleasure that he derived from indulging himself in them. It was with this view that I often took him to dine with me in the city. On these days there was placed on the table a complete collection of his favorite dishes. The first time that he was at such a feast, he expressed transports of joy, which rose almost to frenzy: no doubt lie thought lie should not sup so well as he had dined; for he did not scruple to carry away, in the evening, on bis leaving the house, a plate of lent iles which he had stolen from the kitchen: I felt great satisfaction at the result of this first excursion. I had found out a pleasure for him; I had only to repeat it a certain number of times in order to convert it into a leant; this is what I actually effected. I did more; I took care that these excursions should always be preceded by certain preliminaries which mi edit be remarked by him: this I did, by going into his room about four o’clock, with my hat on mvlicad, and his shirt held in my hand. Very soon these preparations were considered as the signal of departure. At the moment I appeared, I was understood; he dressed himself in great haste, and followed me, with expressions of uncommon satisfaction and delight. I do not give this fact as proof of a superior intelligence, since there is nobody that might not object that the most common clog is capable of doing as much. But even admitting this mental equality between the boy and the brute, we must at least allow that an important change had taken place; and those who had seen the Savage of Aveyron, immediately after his arrival at Paris, know that lie was vastly inferior, with regard to discernment, to the more intelligent of our domestic animals. I found it impossible, when I took him out with me, to keep him in proper order in the streets: it was necessary for me either to go on the full trot with him, or make use of the most violent force, in order to compel him to walk at the same moderate pace with myself. Of course, we were, in future, obliged to go out in a carriage: this was another new pleasure that attached him more and more to his frequent excursions. In a short time, these days ceased to be merely days of feasting, in which he gave himself up to the most lively joy; they absolutely became real wants: the deprivation of which, when the interval between them was made a little longer than usual, rendered him low spirited, restless and fretful. That an increase of pleasure was it to him when our visits were paid to the country! I took him not long ago to the seat of Citizen Lachabeaussière, in the vale of Montmorency. It was a very curious and exceedingly interesting’ spectacle, to observe the joy which was painted in his eyes, in all the motions and postures of his body, at the view of the hills and the woods of this charming valley: it seemed as if the doors of the carriage were a restraint upon the eagerness of his feelings; he inclined sometimes towards the one and sometimes towards the other, and betrayed the utmost impatience, when the horses happened to go slower than usual, or stopped for a short time. lie spent two days at this rural mansion; such was here the influence upon his mind, arising from the exterior agency of these woods, and these hills, with which he could not satiate his sight, that he appeared more than ever restless and savage; and in spite of the most assiduous attention that was paid to his wishes, and the most affectionate regard that was expressed for him, he seemed to be occupied only with an anxious desire of taking his flight. Altogether engrossed by this prevailing idea, which in fact absorbed all the faculties of his mind, and the consciousness even of his physical wants, and, rising from the table every minute, he ran to the window, with a view, if it was open, of escaping into the park; or, if it were not, to contemplate, at least, through it, all those objects towards which he was irresistibly attracted, by recent habits, and, perhaps, also by the remembrance of life independent, happy, and regretted. On this account, I determined no longer to subject him to similar trials; but, that he might not be entirely secluded from an opportunity of gratifying his rural taste, I still continued to take him out to walk in some gardens in the neighborhood, the formal and regular dispositions of which have nothing in common with those sublime landscapes that are exhibited in wild and uncultivated nature, and which so strongly attach the savage to the scenes of his infancy. On this account Madam Guerin sometimes took him to Luxembourg, and almost every day to the garden belonging to the observatory, where the oblio'insr civility of Citizen Lemeri allowed him to take a daily repast of milk.

In consequence of these new habits, some recreations of his own choice, and all the tender attentions that were shown him, in his present situation, head length began to acquire a fondness for it. Hence arose that lively attachment which he feels for his governance, and which lie sometimes expresses to her in the most affecting: manner. He never leaves her without evident uneasiness, nor ever meets lier without expressions of satisfaction. Once, after having slipped from her in the streets, on seeing her again he burst into a flood of tears. For some hours, he still continued to show a deep drawn and interrupted respiration, and a pulse in a kind of febrile state. Madam Guerin having then addressed him in rather a reproachful manner, he was again overwhelmed with tears. The friendship which he feels for me is much weaker, as might naturally have been expected. The attentions which Madam Guerin pays him are of such a nature that their value may be appreciated at the moment; those cares, on the contrary, which I devote to him, are of distant and insensible utiJlt It is evident that this difference arises from the cause which I point out, as I am myself indulged with hours of favorable reception; they are those which I have never dedicated to his improvement. For instance, if I go to his chamber, in the evening, when he is about to retire to rest, the first thing that he does is to prepare himself for my embrace; then draw me to him, by laying hold of my arm, and making me sit on his bed. Then in general he seizes my hand, draws it over his eyes, his forehead, and the back part of his head, and detains it with his own, a long time, applied to those parts.

People may say what they please, but I will ingenuously confess, that I submit, without reluctance, to all these little marks of infantile fondness. Perhaps I shall be understood by those who consider how much effect is produced upon the mind of an infant, by compliances, apparently trivial, and small marks of that tenderness which nature hath implanted in the heart of a mother; the expression of which excites the first smiles and awakens the earliest joys of life.

Section 4

My fourth object was, to lead him to the use of speech, by subjecting him to the necessity of imitation. If I had wished to have published only successful experiments, I should have suppressed this fourth section from my work, as well as the means which I made use of in order to accomplish my object, as well as the little advantage which I derived from them. But my intention is not to give the history of my own labors, but merely that of the progressive developments which appeared in the mind of the Savage of Aveyron; and, of course, I ought not to omit anything»»; that can throw light on his moral history. I shall, he even obliged to advance, on this occasion, some theoretical ideas; and I hope I shall be pardoned for doing so when it is considered what attention I have paid, that they should be supported upon facts, as well as the necessity under. which I felt myself of answering such inquiries as these: “Does the savage speak?” “ If he is not deaf, why does he not speak?” It may easily be conceived, that, in the bosom of forests, and far from the society of every rational being, the ear of our savage was not in the way of experiencing any other impression than those which were made upon it by a very small number of sounds, which were in general connected with his physical wants. It was not, in such a situation, an organ that discriminates the various articulate modifications of the human voice: it was there simply an instrument of self-preservation, which informed him of the approach of a dangerous animal, or of the fall of some wild fruit. It is evident, that the car is confined to certain offices, when we consider the little or no impression which was produced upon this organ, for a whole year, by all the sounds and noises which did not interest his own particular wants; and, on the other hands, the exquisite irritability which this sense exhibited concerning those things that had any relation to his necessities. When, without his knowledge of it, I plucked, most cautiously and gently, chestnut or walnut: — when I only touched the key of the door which held him captive, he never failed instantly to turn back, and run towards the place whence the noise arose. If the hearing did not express the same susceptibility for the sounds of the human voice, for the explosion even of firearms, it may be accounted for from that organ being little sensible and attentive to any impressions except those to which it had been long and exclusively accustomed*.

If I had wished to have published only successful experiments, I should have suppressed this fourth section from my work, as well as the means which I made use of in order to accomplish my object, as well as the little advantage which I derived from them. But my intention is not to give the history of my own labors, but merely that of the progressive developments which appeared in the mind of the Savage of Aveyron; and, of course, I ought not to omit anything»»; that can throw light on his moral history. I shall, he even obliged to advance, on this occasion, some theoretical ideas; and I hope I shall be pardoned for doing so when it is considered what attention I have paid, that they should be supported upon facts, as well as the necessity under. which I felt myself of answering such inquiries as these: “Does the savage speak?” “ If he is not deaf, why does he not speak?”

It may easily be conceived, that, in the bosom of forests, and far from the society of every rational being, the ear of our savage was not in the way of experiencing any other impression than those which were made upon it by a very small number of sounds, which were in general connected with his physical wants. It was not, in such a situation, an organ that discriminates the various articulate modifications of the human voice: it was there simply an instrument of self-preservation, which informed him of the approach of a dangerous animal, or of the fall of some wild fruit. It is evident, that the car is confined to certain offices, when we consider the little or no impression which was produced upon this organ, for a whole year, by all the sounds and noises which did not interest his own particular wants; and, on the other hands, the exquisite irritability which this sense exhibited concerning those things that had any relation to his necessities. When, without his knowledge of it, I plucked, most cautiously and gently, chestnut or walnut: — when I only touched the key of the door which held him captive, he never failed instantly to turn back, and run towards the place whence the noise arose. If the hearing did not express the same susceptibility for the sounds of the human voice, for the explosion even of firearms, it may be accounted for from that organ being little sensible and attentive to any impressions except those to which it had been long and exclusively accustomed*.

- In order to give more force to this assertion, it may be observed, that, in proportion, as man advances beyond the period of his infancy, tiro exercise of his senses becomes, every day, less universal. In the first stage of his life, he wishes to see everything, and to touch everything; he puts into his mouth everything that is given to him; the least noise makes him start: his senses are directed to all objects, even to those which have no apparent connection with his wants. In proportion to his ad \a:>cement beyond the stage of infancy, during which is carried on, what may be called the apprenticeship of the senses, objects strike him only) so far as they happen to be connected with his ap.

It may be easily conceived, then, why the ear, though very apt to perceive certain noises, may yet be very little able to discriminate the articulation of sounds. Besides, in order to speak, it is not sufficient to perceive the sound of the voice; it is equally necessary to ascertain the articulation of that sound: two operations which petites, his habits, or his inclinations. Afterward, it is often found, that there is only one or two of his senses which awaken his attention. He becomes, perhaps, a musician, who, attentive to everything that he hears, is indifferent to everything which he sees. Perhaps he may turn out a mere mineralogist, or a botanist, the first of whom, in a field fertile in objects of research, can see nothing but minerals; and the second, only vegetable productions. Or he may become a mathematician without ears, who will be apt to say, after having been witness to the performance of one of the tragedies of Racine; “what is it that all this proves?"

If, then, after the first years of infancy, the attentions are very distinct, and require the organ to be in very different conditions. For the first, there is a need only for a certain degree of sensibility in the nerve of the ear; the second requires a particular modification of that sensibility. It appears possible, then, that those who have ears well organized, and duly sensible, may still be unable to seize the articulation of tion is naturally directed only to those objects which have some known and perceived connection with our tastes, the reason may be easily conceived why our young savage, feeling only a small number of wants, was induced to exercise his senses only on a small number of objects. This, if I mistake not, was the cause of that perfect inattention which struck everybody on his first arrival at Paris; but which, at the present moment, hath almost altogether disappeared, evidently because he has been made to feel his connection and dependence upon all the new objects which surround his words. There are found, among* the Cretans, a great number of persons who are dumb and yet not deaf. Among the pupils of Citizen Si card there are several children who hear perfectly well the sound of a clock; a clapping* of hands; the lowest tones of a flute or violin, and who, notwithstanding, have never yet been able to imitate the pronunciation of a single word, even when loudly and slowly articulated. Thus, it appears, that speech is a kind of music to which certain ears, although well organized in other respects, may be insensible. The question is, whether this is the case of the child that we are speaking of. I do not think it is, although my favorable opinion rests on a scanty number of facts. It is true that my experiments, with a view to the ascertaining of this point, have not been numerous, and that I was for so Ion" a time embarrassed concerning the inode of conduct that I ought to pursue, that I restricted myself to the character of an observer. What follows is the result of my observations.

During: the four or five first months of his residence at Paris, the Savage of Aveyron appeared sensible only to those particular sounds to which I have already alluded. In the month Frimaire he appeared to understand the human voice, and, when in the gallery that led to his chamber, two persons were conversing, in a high tone, he often went to the door, to be sure if it was properly secured: and he was so attentive as to put his finger on the latch to be still farther satisfied. Some time afterward, I remarked that he distinguished the voice of the deaf and dumb, or rather, the guttural sound which continually escapes them in their amusements, lie seemed even to be able to ascertain the place whence the sound came, for, if he heard it whilst he was going down the staircase, he never failed to reascend, or to descend more precipitately, according as the noise came from below or above.

At the beginning of the month Nivôse, I made a remark still more interesting. One day whilst he was in the kitchen, busy in boiling potatoes, two persons, behind him, were disputing with great warmth, without his appearing to pay the least attention to them. A third came in, who joined in the discussion, and began all his replies with these words: “ Ok! it is different.” I remarked, that every time this person permitted lus favorite exclamation to escape him, “ Oh!" the Savage of Aveyron suddenly turned his head. I made, in the evening, about the hour of his going to bed, some experiments with regard to this particular sound, and I derived from them very nearly the same results. I tried all the other vowels without any success. This preference for o induced me to give him a name, which, according to the French pronunciation, terminates in that vowel. I made the choice of that of Victor. This name he continues to have, and when it is spoken in a loud voice, he seldom fails to turn his head or to run to me. It is, probably, for the same reason, that, he has since understood the meaning t s> atl ^ e monosyllable no } which I often make use of, when I wish to make him correct the blunders which he is now and then guilty of in our little exercises and amusements. Whilst these developments of the organ of the hearing were going on, in a slow but perceptible manner, the voice continued mute, and was unable to utter those articulate sounds which the ear appeared to distinguish; at the same time the vocal organs did not exhibit, in their exterior conformation, any mark of imperfection; nor was there any reason to suspect it in their interior structure. There was indeed observable, on the upper and anterior part of the neck, a scar of considerable extent, which might excite some doubt with regard to the soundness of the subjacent parts, if the suspicion were not done away by the appearance of the scar. It seems in reality to be a wound made by some cutting* instrument; but, by observing its superficial appearance, I should be inclined to believe that it did not reach deeper than the integuments and that it was united by what surgeons call the first intention. It is to be presumed that a hand more disposed than adapted to acts of cruelty, wished to make an attempt upon the life of this child; and that, left for dead in the woods, he owed, to the timely succor of nature, the speedy cure of his wound; which could not have been so readily effected, if the muscular and cartilaginous parts, belonging to the organ of voice, had been divided. fins consideration leads me to think, that v hen the ear began to perceive some certain sounds, if the voice did not repeat them, it was not on that account fair to infer any organic lesion; but that we ought to ascribe the fact to the influence of unfavorable circumstances. The total disuse of exercise renders our organs inapt for their functions, and if those already formed are so powerfully affected by this inaction, what will be the case with those, which are growing aucl developing without the assistance of any agent that was calculated, to call them into action? Eighteen months at least are necessary, of careful and assiduous education, before a child can lisp a few words: have we then a right to expect, that a rude inhabitant of the forest, who has been in society only fourteen or fifteen months, five or six of which he has passed among the deaf and dumb, should have already acquired the faculty of articulate speech! Not only is such a thing impossible, but it will require, in order to arrive at this important point of his education, much more time, and much more labor, than is necessary for children in general. This child knows nothing; but lies and possesses, to an eminent degree, the susceptibility of learning everything. an innate propensity to imitation; excessive flexibility and sensibility of all the organs; a perpetual motion of the tongue; a consistency almost gelatinous of the larynx: in one word, everything concurs to aid the production of that kind of articulate and almost indescribable utterance, which may be regarded as the involuntary apprenticeship of the voice: this is still farther assisted by occasional coughing and sneezing, the crying of children, and even their tears, those tears which we should consider as the marks of a lively excitability, but likewise as a powerful stimulus, continually applied, and especially at the times most seasonable for the simultaneous development of the organs of respiration, voice, and speech. Let these advantages be allowed to me, and I will answer for the result. If it is granted me, that we ought no longer to depend on the youth of Victor; that we should allow him also the fostering resources of nature, which can create new methods of education when accidental causes have deprived her of those which she had originally planned. At least I can produce some facts which may justify this hope.

I stated, at the beginning of this section, that it was my intention to lead him to the use of speech. Being convinced, by the considerations thrown out in these two last paragraphs, and by another not less conclusive, which I shall very soon explain, that it was necessary only to excite, by degrees, the action of the larynx, by the allurement of objects necessary to his wants. I had reason to believe that the vowel o was the first understood; and I thought it ver\ fortunate for my plan, that this simple pronunciation was, at least in sound, the sign of one of the wants most frequently it It by tins child. However, I could not derive any actual advantage iiom I I iis favorable coincidence. In vain, even at those moments when Ins thirst was most intolerable, did I frequently exclaim eau, cau, bringing before him a glass of water: I then gave the vessel to a person who was near him, upon his pronouncing the same word; and regained it for myself ' t m cx P ression: the poor child tormented himself in all kinds of ways; betrayed a desire for the water by the motion of his arms; uttered a kind of hissing, but no articulate sound. It would have been inhuman to have insisted any longer on the point. I changed the subject, without, however, changing my method. My next endeavors were concerning the word lait. On the fourth day of this my second experiment, I succeeded to the utmost of my wishes; Ï heard Victor pronounce distinctly, in a manner, it must be confessed, rather harsh, the word lait, which he repeated almost incessantly: it was the first time that an articulate sound had escaped his lips, and of course, I did not hear it without the most lively satisfaction. I nevertheless made afterward an observation, which deducted very much from the advantage which it was reasonable to expect from the first instance of success. It was not till the moment, when, despairing of a happy result, I had actually poured the milk into the cup which he presented home, the word lait escaped him again, with evident demonstrations of joy; and it was not till after I had poured it out a second time, by way of reward, that he repeated the expression. It is evident from hence, that the result of the experiment was far from accomplishing my intentions; the word pronounced, instead of being the sign of a want, it appeared, from the time in which it was articulated, to be merely an exclamation of joy. If this word had been uttered before the thing that he desired had been granted, my ob ject Mould have been nearly accomplished: then the true use of speech Mould have been soon acquired by Victor; a point of communication would have been established between him and me, and the most rapid progress must necessarily have ensued. Instead of this, I had obtained only an expression of the pleasure which he felt, insignificant as it related to himself, and useless to us both. In fact, it was merely a vocal sign of the possession of a thing. But this, I repeat it, din not establish anv communication between us; it could not be considered as of any great importance, as it was not subservient to the wants of the individual, and was subject to a great number of misapplications, in consequence of the daily-changing sentiment of which it became the sign. The subsequent results of this misuse of the word have been such, as I feared would follow: it was generally only during the enjoyment of the thing, that the word lait was pronounced. Sometimes he happened to utter it before, and at other times a little after, but always without having any view in the use of it. I do not attach any more importance to his spontaneous repetition of it when he happens to wake during the night.

After this result, I totally ren '.meed the method by which I obtained it, waiting for a time when local circumstances will permit me to substitute another in its place, which I think will be more efficacious. I have abandoned the organ of voice to the influence of imitation, which, although weak, is not, however, altogether extinct, as appears from some little advancements that he has since made.